Fred Fawcett and the Eve of Peace

"Buck up old sport, the war will soon be over altogether, and then we shall have you back home again for good."

By all accounts, Fred Fawcett was a beloved son and brother hailing from Blackpool, Lancashire. Born in 1894, he was a model youth who enjoyed the experience of coming from a close, loving family, who were very religious. As a teenager, he balanced work as a designer with evening art classes on subjects such as model drawing.1 He later would work for high-class stores making hand-painted signs.

In November 1906, missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began organising a congregation in Fred’s hometown of Blackpool. Some of his siblings had been baptised in 1899, and Fred, along with some of his other siblings and his mother, followed suit in December 1906. More family members joined later. In the years that followed some of the Fawcett’s emigrated to North America, while others remained in Lancashire, including Fred. The establishment of the Church in Blackpool faced overwhelming opposition, as evident in a municipal meeting held on May 6, 1907, which debated allowing Latter-day Saint missionaries to preach on the beach but was resoundingly rejected.2 When the war broke out in August 1914, Fred was one of approximately 800 members of the Liverpool Conference spread across a swathe of Lancashire.3

In 1914, Fred enlisted with the army and was soon part of the Duke of Lancaster’s Own Yeomanry as a cavalryman. At 11.30 pm on 26 April 1915, Fred was on guard duty looking after the horses near his depot in Preston when he wrote to his sister, Lilian. He mentioned that he expected to soon go to the Balkans to fight against the Ottoman Empire. He expressed his view that a cavalry unit was not as necessary in France due to much of the fighting taking the form of trench warfare.

Fred was deeply affected by the accounts of atrocities and murder he heard from Belgian refugees in England, which fueled his resentment towards the Germans. However, he clarified to his sister that he was not inherently violent and would only defend himself if attacked. As he noted to his sister:

I hope you do not think your brother a bloodthirsty wretch. I would not hurt a fly unless it attacked me first, then it would have sealed it’s doom…

Despite his initial expectations of serving in the Balkans, Fred found himself deployed to the Western Front a few weeks later.

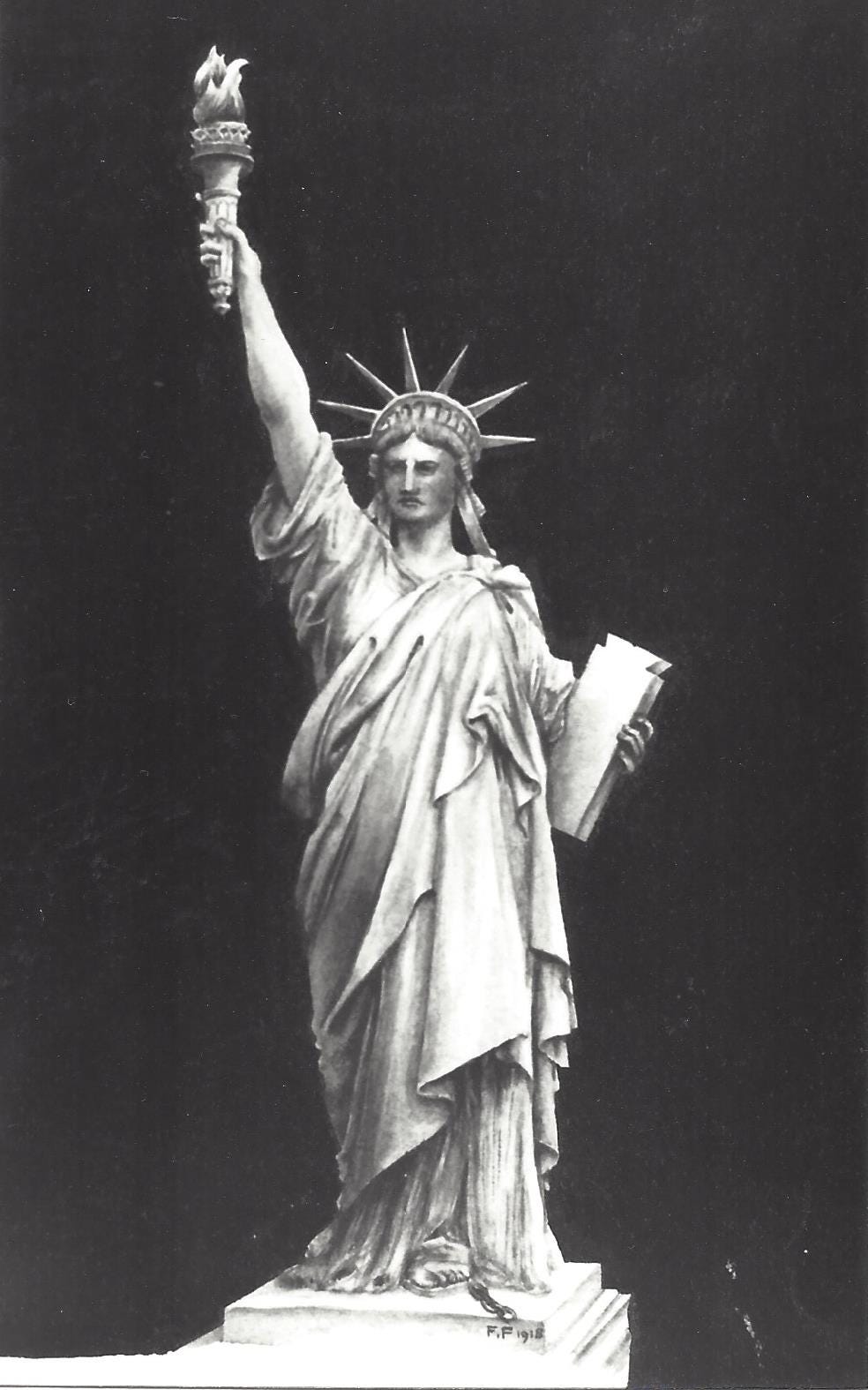

I dare do all that becomes a man, He who dares more is none.

April 1915 - a line from Macbeth that he shares with one of his sisters when sending the above photograph to her.

‘…it will make a man of me if the Lord helps me to hold my willpower + bless me with his Holy Spirit.’

In due course, Fred's ambition and enthusiasm led him to volunteer for various combat roles, including bomb-throwing, machine gunner, sniper, and observer. He also applied for a commission in the Royal Field Artillery but was informed that the only accepting transfers at the time were for the Royal Flying Corps. Fred displayed considerable enthusiasm and zeal in his military service, firmly believing that the Lord was on his side and would protect him.

In due course, Fred’s application to transfer was accepted and he travelled to Brasenose College, Oxford, to study and train to be a pilot. While there he had three exams which were scored out of 100. He aced two of them with 100/100 and in the third exam he scored 85 resulting in 285/300 overall. Fred’s father, Whittaker, wrote to one of Fred’s sisters about her brother’s success:

So you see your brother is no dummy he is expecting his final about now…they are working them very hard they have to learn as much now in 6 or 8 weeks as they used to learn in 2 or 3 years…he was home for a week at Christmas in his flying clothes and I tell you he looks fine and I am glad to say he has no swank but just the same old Fred.4

Throughout his military service, Fred appears to have been an active member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as far as he was able. In September 1917 he spoke at the evening session of a conference held for Church members in Nelson, Lancashire.5 Fred lived between Nelson and Blackpool at various times. He is recorded as living in Nelson in 1911 with his sisters as boarders at a property, but his service record lists Blackpool as his permanent abode. His sisters are mentioned as singing at various events and he is described by family members as a very faithful member of the Church who kept the commandments even while living in trenches on the Western Front. His faith and resoluteness in the faith he accepted as a twelve-year-old stood out to them.6

The Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Air Force

Two months after speaking in Nelson, Fred was back on the South Coast of England. He wrote to some relatives in which he exuberantly shared some good news.

I suppose you know I have been RECOMMENDED FOR A COMMISSION IN THE ROYAL FLYING CORPS. Will tell you all about it in a letter which you may expect in the course of a week or so.7

The ambitious and committed young man had made a breakthrough and was now a commissioned officer. A few months later and the Royal Flying Corps was amalgamated into the Royal Air Force in April 1918.

After his commission as a Second Lieutenant in September 1918 Fred would have been flying sorties over France. Family records note that he was a survey pilot who viewed the enemy lines and drew plans of trenches and other defences for leaders to use when making plans and to spot enemy movements. As the war continued, however, the Royal Air Force adopted a new military doctrine in which tanks and aeroplanes were used in greater coordination.8 The planes would disrupt and dislodge targets and threats as the tanks trundled towards the trenches. In October 1918, Fred received his first posting and was transferred to the 64 Squadron of the Royal Air Force for overseas active service in France.

1 November 1918

As October turned to November there was constant talk about the end of the war. Events were falling into place which made the end with an Allied forces win seem inevitable. Bulgaria surrendered in September and the Ottoman Empire capitulated on 30 October. As the war was coming to an end the Austro-Hungarian Empire began imploding as various nationalist elements of minority ethnic groups declared independence amidst the chaos caused by a pressing Italian army who sought to punish the Austro-Hungarians.

On November 1, 1918, a Friday, the weather was fair but with poor visibility. According to historical reports, hostile aircraft were moderately active throughout the day. Despite the misty weather, the pilots and aircrews of the 64 Squadron persevered, performing surveillance missions and conducting ground attacks from low altitudes. They carried out bombing patrols targeting German positions in and around Valenciennes, supporting the Canadian Corps.9

The available records are not clear, but Fred appears to have been one of the pilots in action that day when something went wrong. It appears that Fred’s plane “came down badly damaged” which resulted in a fire. Whether it was a training incident or active service Fred was urgently transported to a hospital in Camiers, France, for treatment.

The Reaction

Fred’s sister, Ruth, wrote to him on 11 November 1918, shortly after finding out he was injured and on the same day of the armistice. Whatever news had reached her she knew he was injured and she seemed to think that he was recovering and would make it back to full health. The following extract is from her letter:

Dearest Brother,

Buck up old sport, the war will soon be over altogether, and then we shall have you back home again for good. Oh Brother mine, I wish I could have been with you today. Just to celebrate peace. That would have been the best way of celebration for me.

We have all been sent home from work for a day, and the people nearly went mad with joy. I was alright Fred until I saw an aeroplane, and that was my kill joy. Anyway Freddy dear, you are going to pull through, and come home, and then we shall all go to America to see our girls, and that will be our rejoicing day…The day we are all together for good.

…I will write again later. You know Fred you must try and be home for Xmas. We can’t do without you, you know.

Just imagine yourself kissed hundreds of times in honour of peace. Won’t it be awful for the boys who got killed the last few minutes of the war? I shall thank God every hour Fred that you have been spared to us. There will be some rejoicing, and some sorrowing all over today. To think you have been one of the chosen few to come through this terrible ordeal. Really we have something to be thankful for.

Unknown to Ruth, as she wrote the letter Fred lay dying from his wounds. He may well have known that peace had finally been achieved, but he was about to find his own peace. Fred finally succumbed to his wounds on 12 November 1918, the day after the armistice was signed. His death was the bitterest of pills for his family and friends to swallow. A beloved son, brother, and friend was gone, snatched away at the final moment in a cruel twist of fate. One can only imagine the tears that were shared when the news reached home.

Memorialisation

Despite Fred's devout adherence to the gospel and his commitment to his country, he was never officially recognized as a Latter-day Saint casualty of the First World War. This was likely due to the closure of the Blackpool branch before the war, making it difficult for him to attend meetings regularly. The Fawcett family, in the absence of a Latter-day Saint congregation, had been attending Wesleyan meetings. His sister, Ruth, who later emigrated to Utah, wrote to him during the war and mentioned that she had attended a Wesleyan meeting on account of it being Temperance Sunday.

In the absence of a Latter-day Saint congregation in Blackpool the family appear to have attended Wesleyan meetings. On 2 April 1919, a service was held at the Adelaide Street Wesleyan Church in Blackpool. A welcome home gathering was held in the schoolroom for 120 men belonging to the Church who were now discharged or demobilised. The event was one of general happiness as most of the men had returned safely. Food and speeches were given throughout the night for the men and their families. A note of sadness, however, filled the room when the names of those who had offered the supreme sacrifice were read out, Fred’s name being among them.10

Local newspapers shared his obituary which noted that up until that point, after four years of warfare, Fred had been without injury.11 After less than two weeks in active service with the RAF, he was gone, a victim of the dice of life. According to his and his family's beliefs, Fred was called to a new labour, to work with those who had already died. According to one sister he wanted to serve a mission for the Church and travel to Utah.

For over a century, Fred's faithful obedience to the gospel and his dedication to his country had largely faded from memory. Thanks to the efforts of his sisters’ descendants, his life, marked by rich experiences and selfless sacrifices, can now be remembered by his fellow believers as that of a man of faith, courage, and love.

Thank you for reading. If you liked this post please consider sharing it with someone who you think might enjoy reading about Fred and his sad tale.

‘Board of Education,’ Nelson Leader, 28 July 1911, p. 8.

‘A Municipal Mixture,’ Fleetwood Chronicle, 10 May 1907, p. 5.

Liverpool Conference Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1840-1950, 25 December 1914, LR 4949 2, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

Letter from Whitticker Fawcett to Lillian Wilkie, 3 January 1917.

‘From the Mission Field,’ The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, Vol. 79, No. 41 (1917), p. 656.

Olive Hawkins, ‘Whitaker Fawcett and Mary Ellen Mason,’ unpublished family history.

Letter from Fred Fawcett to Lilian and Richard Wilkie, 11 November 1917.

A. D. Harvey, ‘The Royal Air Force and Close Support, 1918-1940,’ War in History, Vol. 15, No. 4 (2008), pp. 466-468.

RAF Communiqué No 31: 1 November 1918, published 2 November 1918.

‘Wesleyan Welcome,’ Fleetwood Chronicle 4 April 1919, p. 10.

‘Airman’s Tragic Death,’ Blackpool Gazette and Herald, 22 November 1918, p. 8; ‘Blackpool Airman’s Death,’ Blackpool Times 23 November 1918, p. 5; and ‘Fylde Heroes of the War,’ Blackpool Herald and Fylde Advertiser, 29 November 1918, p. 3.

Great essay James! What's so tragic is that military leaders knew that the ear was almost over yet they kept sending out troops.