A Latter-day Saint Cipher

Samuel Richard's 1858 proposal

Pigpen

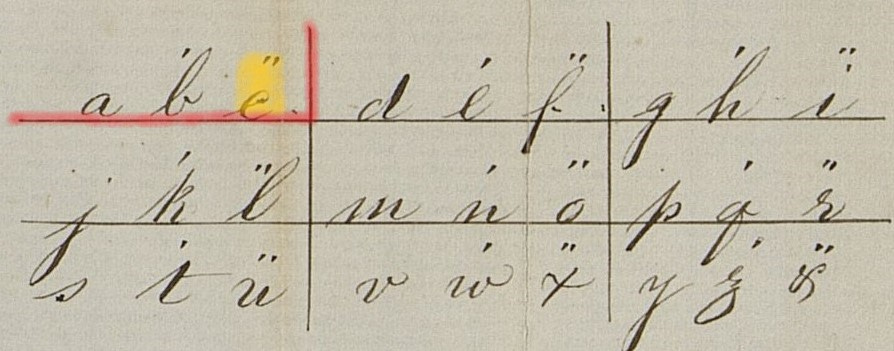

In a letter dated 9 August 1858, Samuel W. Richards wrote to Brigham Young to introduce a method for obfuscating written communications to prevent others from intercepting sensitive information. The cipher, which had been developed by William Budge, broke the Latin alphabet into a grid of nine squares with three letters in each segment (with the final segment containing an ampersand). This form of substitution encryption is referred to as a ‘pigpen cipher.’

A Pigpen cipher, which is also known as the Freemason cipher, is a basic and simple encryption method that with today’s technologies and understanding is easily deciphered. It swapped letters for symbols in a way to complicate the message and prevent someone from reading the contents. In most cases, however, it was relatively distinguishable and could be deciphered with relative ease. The origins of the cipher are murky with attribution to Jewish rabbis or the Knights templar. The cipher was so popular within Masonic fraternities that the system eventually became associated with Freemasonry.

How it works

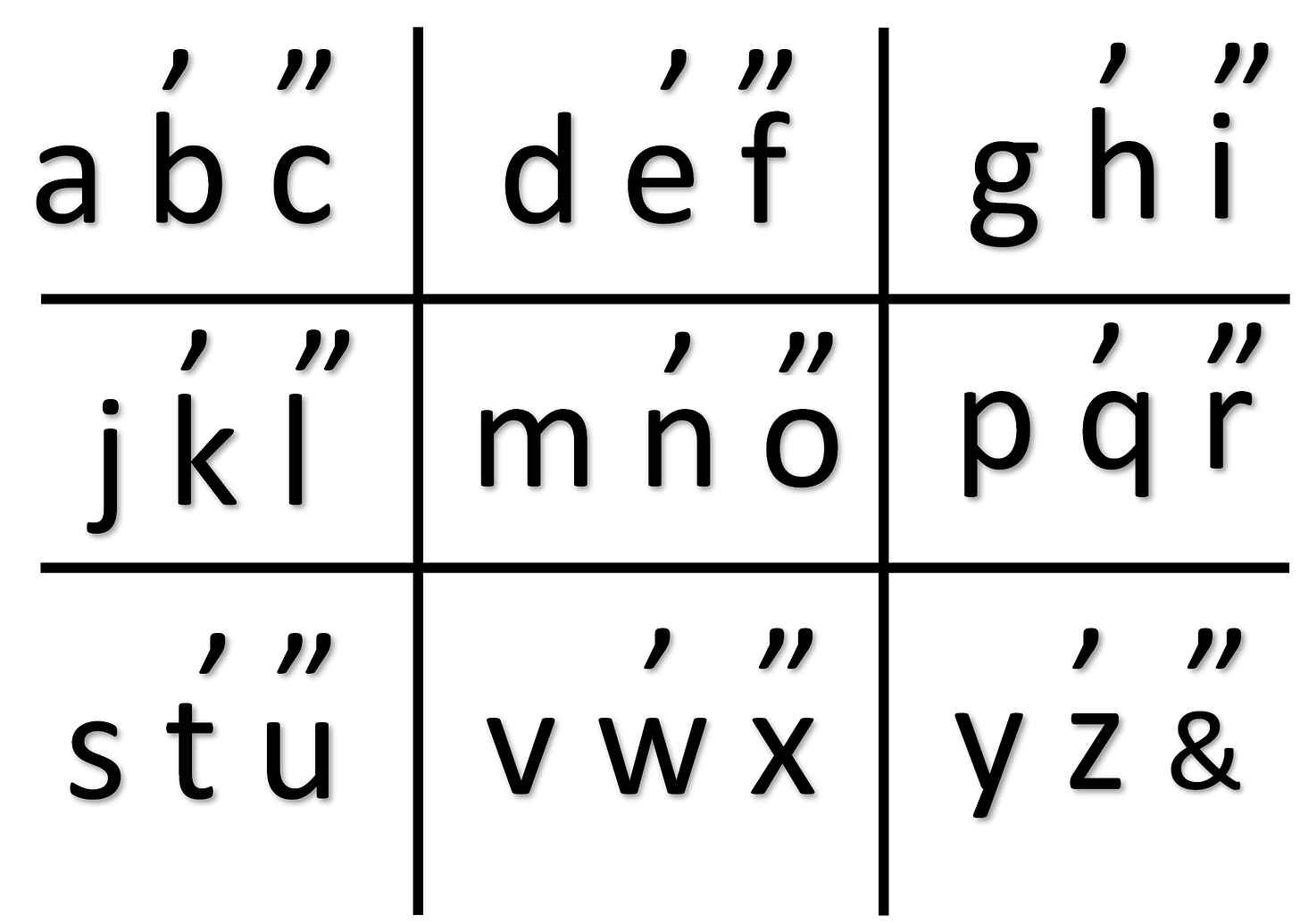

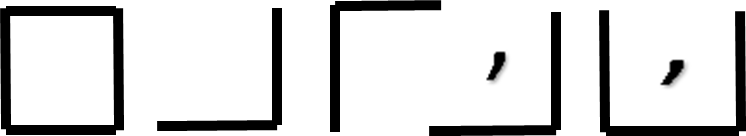

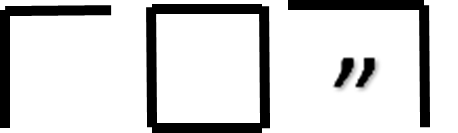

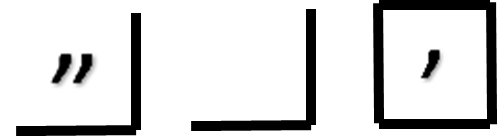

Each letter of the plaintext (the uncoded message) is replaced by a non-alphabetic set of symbols that follows a set pattern. The cipher is composed of two elements: aspects of the underlying grid and either no mark, a single mark, or a double mark.

So if we wanted to start with the letter “C” we would create a symbol using the sections underlying grid structure, which in the below example would be a horizontal line with a vertical one on the right. Because “C” is the third letter in the section we use a double mark (”) inside the symbol and get something like this:

There were of course limitations to the system. First, it would only ever work on written communications. Second, anyone familiar with pigpen ciphers would soon be able to work out the pattern and thus be able to decode the message. Third, you had to ensure that the other person knew how to decipher the message.

As Samuel Richards noted in his letter to Brigham Young:

The Diagram is subject to many variations should the present form of it be discovered so universally as to destroy its utility.

Usage

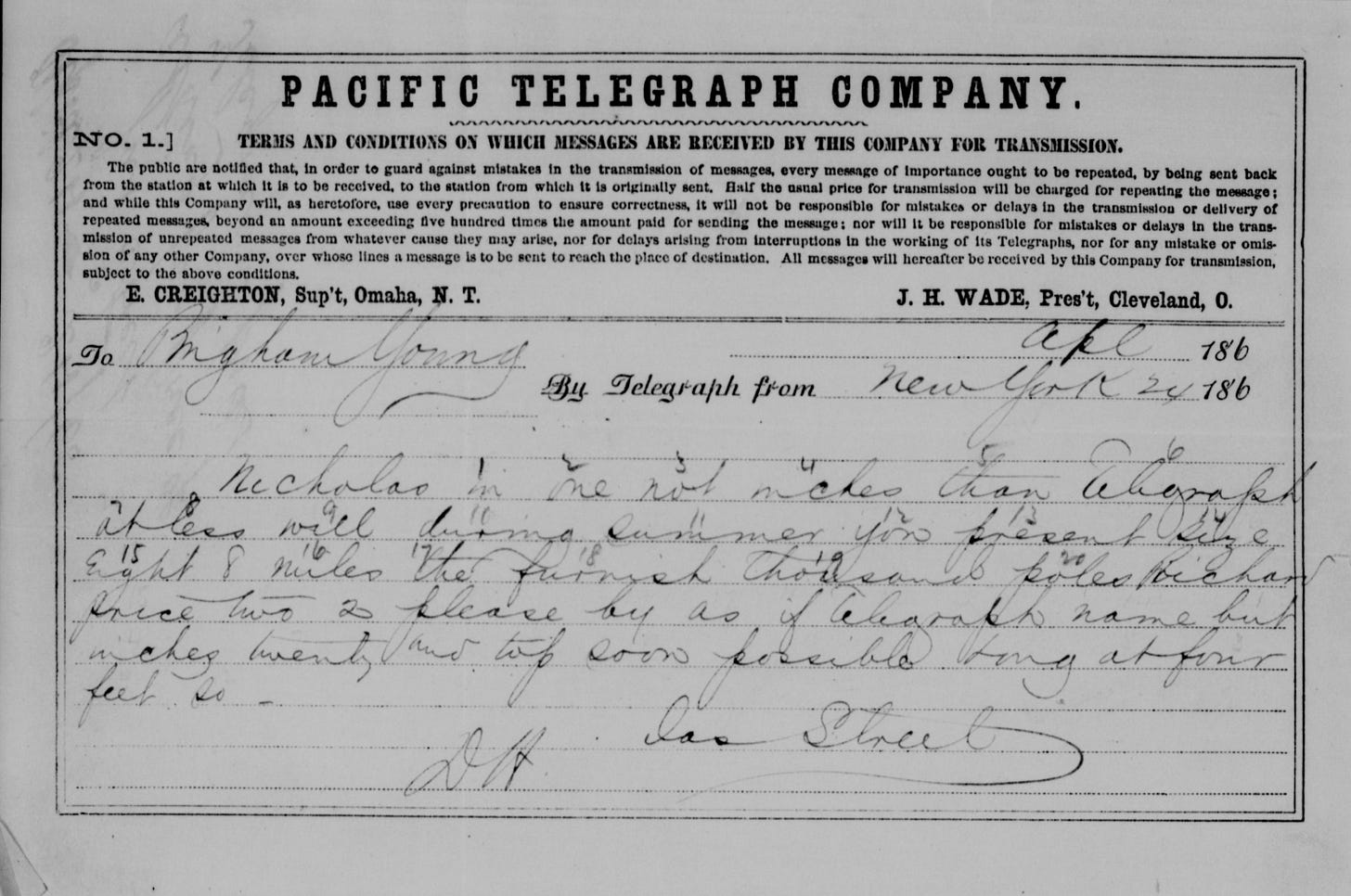

In 1871, William Dougall sent word to Brigham Young to warn him about “gentile operators” who were looking to intercept Church communications being sent and received by telegram.1 To protect againt this he encouraged him to use ciphers to encode communications. Telegrams were particularly vulnerable to interception from a third party and various members and leaders used other methods of substitution encryption to protect the security of the message. A typical system used in the nineteenth century was a Caesar cipher, which was a substitution method that the plaintext is switched into an alphabet where the letters are moved a certain number of times.

In the above example, the letters are moved to the left three times. Thus a “D” becomes an “A”, an “E” becomes a “B” and so on.

Members and leaders used different systems for encoding messages, but this became increasingly important for those practising plural marriage who needed to send messages but avoid detection. The system was used to some extent but only in a limited manner. Other surreptitious communication methods, such as writing in Hawaiian, were adopted also. At a time when fears of surveillance abounded and the threat of imprisonment loomed around every corner the need to safeguard information became a prominent concern.

Activity

Using the cipher key above, try unscrambling this coded message. Let me know in the comments if you can work it out and what you think of this secret system.

Enjoy!

Telegram from W. B. Dougall to Brigham Young, 9 November 1871, CR 1234 1, bx. 46, fd. 5, CHL.