An Unexpected Visit from a Well Dressed Gentleman

Who was the 'Well Dressed Gentleman'?

Oliver Budge is one of thousands of Latter-day Saint men and women who have, over the last almost 200 years, paused their lives to serve as missionaries in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1933 he had spent the last three years or so as president of the German-Austrian Mission, which was headquartered in Berlin, Germany.

Things were going well in the German-Austrian mission despite ongoing political developments. In September 1933 he wrote a letter to missionaries who had concluded their service.

“All organizations in the “Buro” are fully organized with a president, counselors, and a secretary, all of whom, except three, are German brothers and sisters. It is wonderful how they acquit themselves in whatever they undertake to do. About 82 percent of the branches are now in the hands of the local brethren, and they are, generally speaking, doing a fine work. It will be remembered that in this mission, and while you were here, we all agreed to give close attention to the training of Priesthood holders. The fruits of our labors are now being realized far beyond what you or I were able to judge at the time. Thanks to you brethren for your faithfulness and efforts in this direction.”1

Sixty-one-year-old Oliver was sitting at his thick wooden desk early one September morning when a “well dressed gentleman” entered his office. After confirming President Budge’s identity the man began speaking:

“I am the Chief of Secret Service. I cannot give you my name, but my station number is II-E, Room 218. For our information, permit me to ask you the following questions. What are you expecting to accomplish in this country? How are you expecting to accomplish it? What are you teaching the people? How do you meet your expenses? What is your attitude toward the government?”2

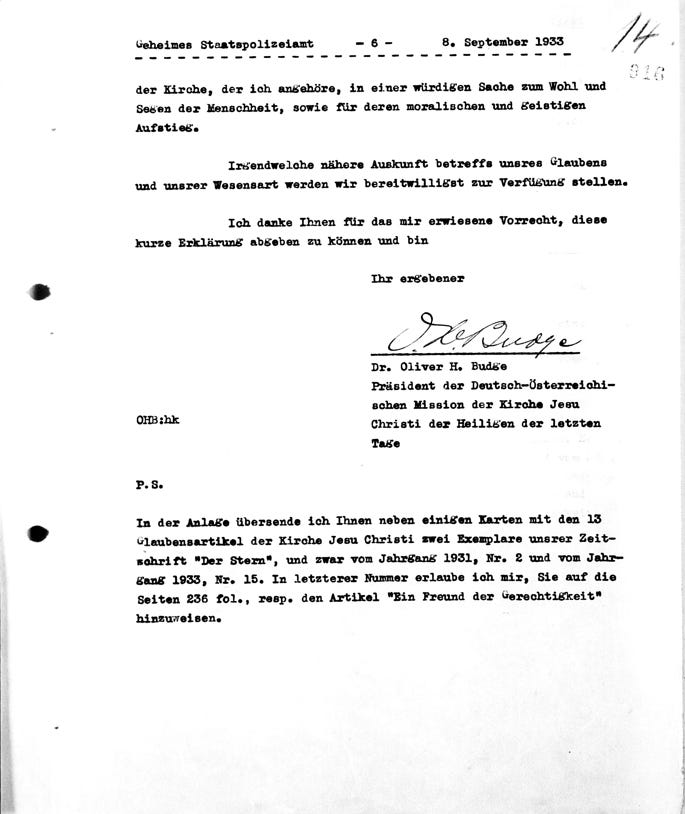

Oliver was a lifelong member of the Church born to a Scottish father who converted to the faith and an American mother who was raised in it. With a lifetime of gospel service and learning behind him he was able to answer the questions satisfactorily. According to Budge the officer was impressed and remarked “If everyone could hear your message it would be most desirable.” After that Oliver presented him with a copy of the Book of Mormon and some other literature. As he was leaving the officer asked Oliver if he would write a brief letter listing what they had discussed, which he agreed to do.

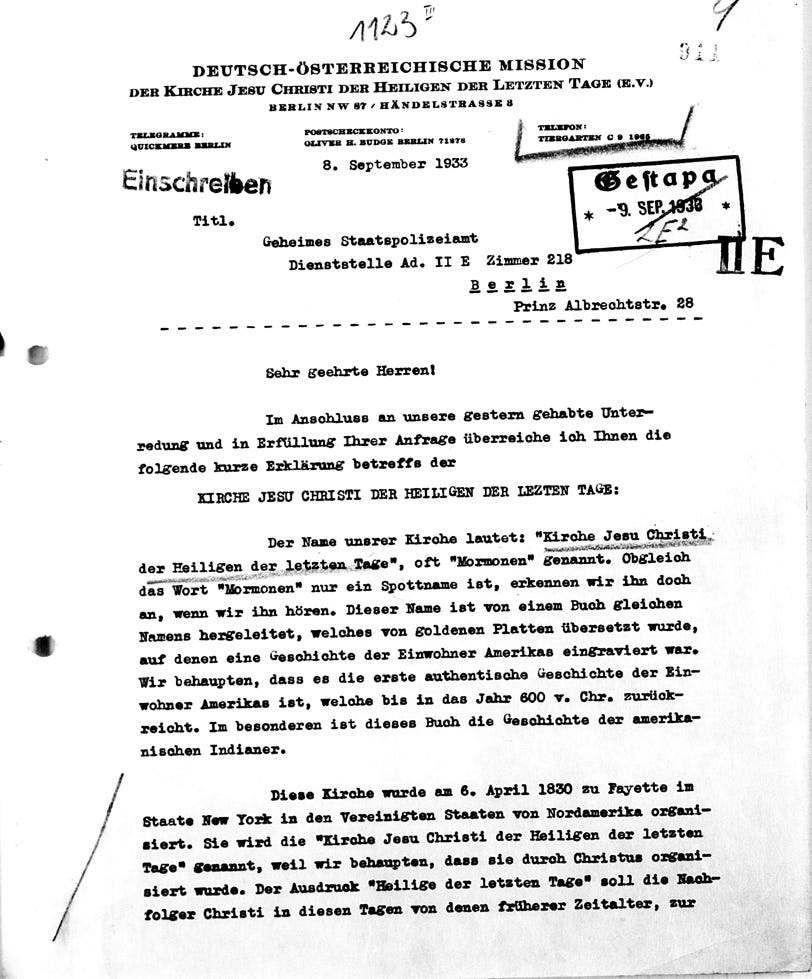

Oliver wrote the letter and sent it the next day, but it is unclear if he ever received a reply. Declassified Gestapo records indicate that other faiths were investigated in a similar manner during 1933.

Who was the well-dressed man?

In June 1933 and January 1934, the Gestapo published two “business distribution plans”, which outlined the department structures and room allocations in the secret police headquarters in Berlin. In 1933 the head of the Gestapo was Rudolf Diels who functioned from April 1933 until April 1934 when he was replaced by Heinrich Himmler. Diels organised the Gestapo into ten departments and the January 1934 distribution plan reveals that Department II-E was a division dedicated to cultural and social policy, aviation, film and radio matters, and religious associations. The head of the department, Karl Wittich, was based in Room 215, with three other employees listed: Police Chief Secretary Starck, Police Secretary Roggon (Room 217), and Criminal District Secretary Jessel (Room 219). Room 218 is not specifically mentioned in the plan.

In August 1933, Karl Wittich, a German civil servant and recently registered member of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nazi), was appointed to the Secret State Police Office to manage Department II E 2, which oversaw cultural and social policies in Germany. Karl had attended school in Wiesbaden along with his classmate and future boss, Rudolf Diels.

It is difficult to confirm the details of President Budge’s encounter, but several other sources note a secret police visit to the Mission Office on 7 September 1933. Declassified Gestapo records show that they preserved the letter he sent them on 8 September 1933.3 The letter was reconsulted some years later when working out what to do with the Church as the Nazis solidified their control of the country.

The well-dressed man appears to have been Karl Wittich. Dr Claudia Steur of the Topography of Terror Museum in Berlin thinks Room 218 may have been a secretaries office or anteroom. Regardless of who the officer was it is clear that the Gestapo ‘Cultural and social policy, aviation, film and radio matters, and religious associations’ division was trying to work out what the Church believed, how it functioned, and what its views about and relationship to the new government was going to be.

President Budge’s Statement

In his report at the end of 1933, Oliver wrote a statement about some of the implications of the Nazi’s rise to power:

I desire to make the following statement regarding the political situation as affecting us as a Church:

Naturally, because of the unsettled political condition of this country and the strong effort they are making to readjust themselves, almost all religious organizations have been affected more or less, including the Catholic and Evangelical churches, the latter being at present divided within itself. Because of the above named conditions we have naturally been interfered with .in a small way. The interference up to date has not come from the government, however, but has been augmented by the ministers of the leading churches.

For instance, upon different occasions members of the new party have felt a self-responsibility, and, without appointment, have either directed or taken some of our missionaries to the police station. This was especially true in the city of Dresden, the missionaries being Elder Reuben A. Ward and Elder Hampton H. Trayner. In Aschersleben Elder J. Walden Hughes, accompanied by Robert S. Budge, was taken into custody by appointed police officers and marched through the streets to the police station, with many citizens following behind them. In both of the above cases the brethren were able to defend themselves by a proper explanation of their work.

In a town near Landsberg a/w, Elder Chancey O. Rowe and Elder Milton L. Fullmer were attached by a preacher who surrounded himself with villagers who were willing and did run these brethren out of the town after abusing them as far as it was possible to do so by word of mouth.

In the city of Hindenburg while Elders P. Blair Ellsworth and Preston C. Allen were giving out tracts from door to door m the usual way, they were attacked by a member of the Nazi party, who, as evidence, wore the regular brown suit. The Nazi man without demanding or permitting an explanation, took his leather belt from his waist, which belt had attached to it a large buckle. With this belt he proceeded to hit Elder Ellsworth over the head, creating rather bad lacerations. Since this Nazi party had taken the responsibility upon himself to fight the brethren and then to take them to the police station, a request was made of the police officers of that city to make an explanation as well as an agreeable settlement in writing to the brethren, but they refused to have anything to do with it.

A few other small things have happened, of which I have not attempted to keep track.

In conclusion I desire to say that so far as the government itself is concerned, we have been treated with courtesy and with full freedom to proselyte, preach and practice our religion.4

Most opposition, therefore, was seemingly coming from other religious groups rather than state-sponsored persecution. This is something that other religious minorities in Germany have alleged for this period. The Nazis, still coming to terms with their rise to power, had to work out where the loyalties of many of these minority groups lay.

Opposition

Still, there had been some persecution and conditions became more difficult. It was not long after the Nazi rise to power in January 1933 that there were localised incidents involving Latter-day Saints. On 3 April 1933 two missionaries, Preston C. Allen and P. Blair Ellsworth, were attacked and beaten by a uniformed Nazi while serving in Hindenburg. The missionaries were out distributing materials when a lady who they had interacted with misrepresented what they were doing to a Nazi official. The man, without any inquiry first, hit Elder Ellsworth over the head with the buckle end of his belt which cut his head. The missionaries were taken to police headquarters where an investigation took place. Elder Ellsworth was given the opportunity to levy charges against the attacker but declined to do so to avoid arousing more trouble for the missionaries.5 Still, conditions were not bad for the Church as a whole. On 19 June 1933 permission was secured from the city of Berlin to hold open-air meetings in the city which led to an increase in people attending meetings.

Things began turning for the worse for Latter-day Saints in early 1934 as Nazi officials began to oppose certain Latter-day Saint teachings, practices, and publications. In January 1934 the missionary tract “Divine Authority” was confiscated by the government and banned from being circulated. A similar step was taken a few weeks later with a tract entitled “Signs of the Great Apostasy.” Oliver Budge felt that the mysterious and unnamed visitor remained “very friendly to us”, but nonetheless some restrictions were being enforced. The Saints pursued a path of loyal yet independent action. After tracts were ceased Oliver asked for an invitation from the government to talk the matter over and to arrive at a favourable conclusion.6

Other incidents demonstrate a Latter-day Saint tendency to comply with laws to the limit in which they needed to occur. For example, at one point a secret police officer visited Wilhelm Meister, President of the Berlin-Ost Branch, and inquired about various matters relating to the Church. The officer had pictures of several missionaries of the Church and he asked Wilhelm to identify them, which he did. A similar incident took place in Eberswalde. A police officer visited the branch president and inquired about the headquarters of the Church and wanted to know where the meetings were held. The precise information was given, as requested, but no more. Nothing nefarious came from the meetings, but it demonstrates how local leaders sought to maintain the peace and avoid creating undue hardships for the Saints.7

Occasionally leaders pushed back. One such case occurred in January 1933 when two police officers visited the mission office to seize copies of, “Signs of the Great Apostasy.” The officers took what was in the office and Oliver assured them that the remaining tracts would be called in from the field. The officers asked to see the storeroom and other materials. Oliver Budge objected mildly with the statement that if they desired to investigate anything beyond the tract, it would only seem right that they produce written authority. The Nazi officials claimed that their uniform was sufficient authority, but he disagreed. At that precise moment, as the men were about to make their way to the storeroom, the telephone rang. On the line was the chief of the department, most likely Karl Wittich, who in a very pleasant and polite manner, informed President Budge that he might expect a call from an officer. Oliver told him that two officers were already present in the office. Karl asked to speak with one. At the end of the conversation between the officers, the one in the office who did the speaking apologized for being a little bit forward. He assured President Budge that they meant no offence. During the conversation between the officers on the telephone it was noted by Karl that the Saints “were honorable and dependable”. Karl also clarified that it would not be necessary for them to do anything but bring the confiscated tract with them.8

Another such instance occurred in late March 1933, when a baptism took place in Grunau, near Berlin. A “keen” observer reported the proceedings to the police and an investigation was opened. Members and friends of the Church were taken to the police office and interrogated. When another baptism was to take place the Saints discovered police officers in position who announced that baptisms could not be held in that location anymore.9

Around that time Church meetings were being held in homes in the village of Leest, near Berlin. Leaders of the village discovered the meetings and banned them from taking place. Elder Herbert Klopfer, from the Mission Office, travelled to the village and asked officials for an explanation for the action. He was told that local religious ministers had discovered that children were forced to attend meetings and that the officials had sought a stop to such practices. After Elder Klopfer explained that no such practice had ever been implemented the mayor promised to report to his superiors. A letter was written to county officials explaining what happened at the meetings. Permission to hold the meetings was once again granted to the Saints.10

Summary

The ensuing years saw an increasingly restrictive environment within which the Church could operate. Although the Church complied with every restriction meted out against it other faiths cried afoul and to ensure equal treatment the Church had additional privileges and opportunities removed by Nazi officials. Certain pieces of literature were banned and many members, missionaries, and leaders were pulled into police stations for interrogation about their activities. Sometimes membership lists were demanded with political affiliations listed for each member.

Oliver Budge’s interaction with Karl Wittich appears to have framed relationships between the new Nazi government and the Church positively. Karl, for the time he was in post at least, provided a measure of protection for the Church and categorised it as an organisation that could be trusted. Although the Church was subject to the whims of Nazi Germany it escaped the brunt of anti-religious oppression that accompanied national socialism. Amidst the uncertainty, leaders sought a path of peaceful coexistence without jeopardising the safety of members or missionaries.

Oliver Budge’s response to the unexpected visit from the well-dressed gentleman had an impact on other Latter-day Saints that he probably did not appreciate at the time. Gestapo reports show that many Nazi officials wanted to shut down The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Germany. However, it seems Oliver’s efforts brought about a degree of tolerance for the Saints from some of the high-ranking officials he had interacted with, which proved a blessing in an age characterised by intolerance and hatred for others.

Oliver H. Budge letter to returned missionaries, 4 September 1933, LR 3167 21, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

Oliver H. Budge letter to David O. McKay, 5 March 1954, MS 3785, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

‘Verschiedene Sekten und Freikirchen,’ Vol. 14, R 58 5686, Bundesarchiv, Berlin, Germany.

German-Austrian Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 1925-1937, Volume 4, Part 2, p. 348. LR 3167 2, bx. 2, fd. 2, CHL.

German-Austrian Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 1925-1937, Volume 4, Part 2, LR 3167 2, bx. 2, fd. 2, CHL.

German-Austrian Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 1925-1937, Volume 4, Part 2, pp. 352-353. LR 3167 2, bx. 2, fd. 2, CHL.

German-Austrian Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 1925-1937, Volume 4, Part 2, p. 353. LR 3167 2, bx. 2, fd. 2, CHL.

German-Austrian Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 1925-1937, Volume 4, Part 2, p. 353. LR 3167 2, bx. 2, fd. 2, CHL.

German-Austrian Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 1925-1937, Volume 4, Part 2, pp. 358-359. LR 3167 2, bx. 2, fd. 2, CHL.

German-Austrian Mission manuscript history and historical reports, 1925-1937, Volume 4, Part 2, p. 359. LR 3167 2, bx. 2, fd. 2, CHL.

Fascinating how a certain book aimed at the church-critical audience makes out that the church was somehow in cahoots with the Nazis, when in reality and at the time, the church was navigating a very difficult political situation. The leadership had to both make sure they did not put missionaries and members at risk, whilst still trying to fulfil the role of the church and promote the cause of Zion. It's easy to look back and forget what peril people were in.. this fantastic article gives a clear reminder of that.