By Sail, Rail, and Trail

The 1860 cross terrain emigration experiences of Norwegian Latter-day Saint Johanna Thomassen

One afternoon in May 1861, as waves lapped against the boat in Copenhagen, Denmark, fifteen-year-old Norwegian Latter-day Saint Johanna Thomassen was waiting for the next stage of her journey to begin. She was about to leave Scandinavia with her mother to travel to Utah in the United States of America, where they could freely live their newfound faith and explore new opportunities in a foreign, exciting land. With only two leather trunks filled with their worldly possessions, which included clothes, church books, schoolbooks, bedding, and oil paintings of relatives, they would be beginning anew.

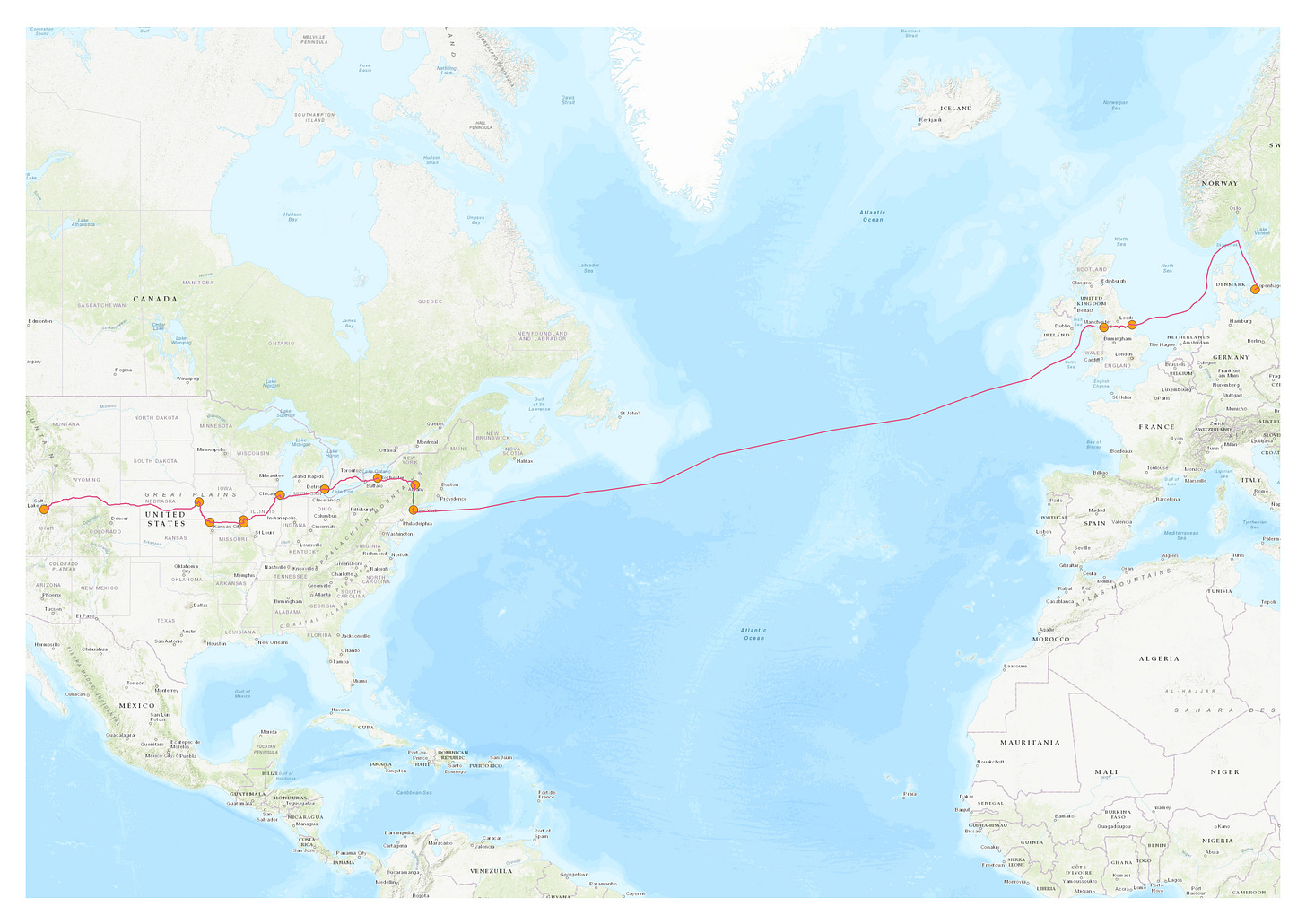

The journey would be long and complicated with many risks and challenges, but thousands of Europeans like Johanna were willing to do it. To start with the ship she was on was due to travel across the North Sea to Grimsby, England. There she and her companions would travel by train across the country to Liverpool where they would board the final vessel, The William Tapscott, to cross the Atlantic to New York.1 In America, she and her emigrant company would continue their journey by steamboat and wagon across the Great Plains. It was going to take months to get there.

Johanna had been raised in a Lutheran home near Drammen, Norway. When her brother, Peter, converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in June 1854 it caused no end of drama and tension in their home and community. Yet he was resolute in his faith. A year later Johanna and Peter’s father, Johan, lay dying in his bed. Peter continued to preach the gospel to Johan who was close to accepting it when he died. Johanna’s mother, Anna, became more receptive to the restored gospel and was baptised in 1856.

In 1858, Peter was serving as a missionary in Norway. While visiting Anna, Johanna, and another sister, he invited them to come and live in Copenhagen with him where he could better care for them. They sold up and moved to Copenhagen soon after, although one sister remained in Norway. Finally, in June 1859, Johanna committed to joining the Church and was baptised by Peter in Copenhagen on what was undoubtedly a happy occasion.

The Gathering + Transmigration

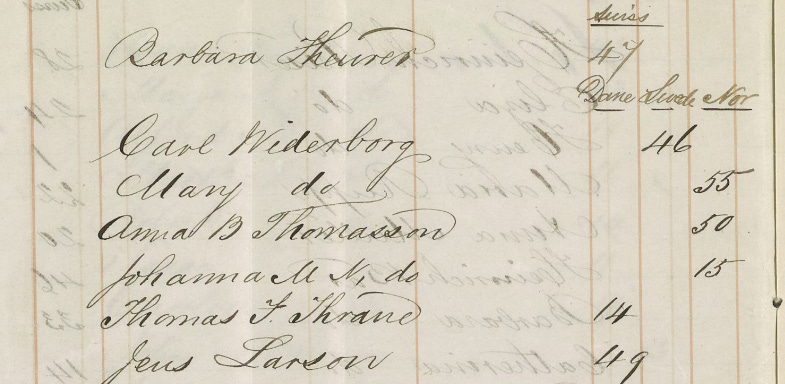

During this period Latter-day Saint leaders often encouraged members to emigrate to Utah. In Copenhagen Johanna and Anna were invited to emigrate with Carl Widerborg, who had been the Mission President for the last two years. He was a native of Sweden who had been baptised in Norway and then served as a missionary there. Later he moved to Copenhagen to work in the mission office. When American missionaries were withdrawn in 1858 he was appointed as president. He was once described as “perhaps the ablest public speaker which the Scandinavian mission has produced up to the present time.”2

Johanna and Anna agreed to travel with Carl and his wife to Utah, but Peter needed to remain in Copenhagen longer with his family. Despite the challenges ahead of them, the 301 Scandinavian Saints would travel together as a unit: men, women, and children. Although some differences in culture and language existed, they were united in their beliefs and dreams of joining the Saints in Utah.

Journeying the 600 miles through the Kattegat and North Sea was rough and some migrants suffered through seasickness. The winds were strong and the ship heaved heavily as it made its way across the sea. They travelled for several days before arriving at Grimsby, a port town in East England. There was a delay in landing due to low water, but by 4 pm they were on English soil, much to the relief of some. The emigrants were then housed in a large emigrant facility at the dock. It was a secure property that served as a type of quarantine but also stopped them from wandering around the town or meeting with locals. They had warm water to clean with and an opportunity to rest.3

The next morning the migrants boarded a train that went direct to Liverpool. Johanna would have been able to gaze out at the passing green British landscape but would have been unable to explore it. They had to get to Liverpool and prepare for the most arduous phase of their journey: an ocean voyage across the Atlantic.

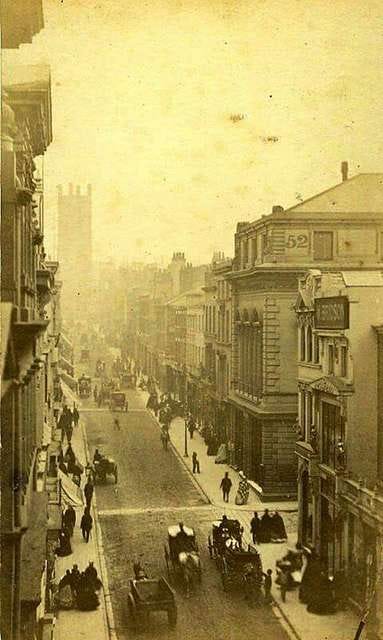

Arriving in Liverpool would have been an eye-opening experience for the young fifteen-year-old Norwegian. Carts hurried by on the roads and people paced down the pavements. The port was also a busy scene. Ships were coming and going carrying goods and people worldwide. Sailors, emigrants, refugees, and others passed through the city on their way to somewhere else with foreign languages and alien smells everywhere. It was a city through which people travelled places to seek fortunes, happiness, and a better future.

Johanna and Anna spent their first night in Liverpool at a hotel on Paradise Street, like other emigrants in their group. The next day, Monday the 7th of May, the emigrants were permitted to board the ship and settle into their quarters. They would then spend the next few days sleeping on the ship waiting for it to sail.

Across the Briny Deep - By Sail

The William Tapscott was a large ship. It was one of the largest full-rigged vessels constructed in Maine during the 1850s and a year earlier it had carried another large group of Latter-day Saint emigrants. Conditions were not to every passenger’s taste, but it was an effective vessel. Ultimately, The William Tapscott was the ship that took the most Latter-day Saints across the Atlantic.

One correspondent who observed Johanna and the other emigrants in Liverpool described the passengers as “all of respectable appearance.”4 On the 10th of May, an inspector and doctor boarded the ship to inspect the emigrants and ensure they were healthy. The passengers passed the inspection and the next day, 11th of May 1860, the ship left Liverpool. The Latter-day Saint emigrants came from across Europe and were led by Elder Asa Calkin, the recently released European Mission President. His counsellors were William Budge and Carl Widerborg, who were experienced Church leaders.

As with most emigrant ships the living arrangements were cramped and uncomfortable. One Swiss emigrant onboard the same ship recorded what it was like to cook onboard:

I had to do some cooking for about 8 persons. I was most of the time sick. By standing before the hot stove stirring the rice which, however, got burned, the kitchen was always crowded by the folks and everything were uncomfortably fixed. I ate very little on board a ship. Our main food was salty pork, rice, and some potatoes. No bread but some hard crackers without salt. I did nearly starve and was very sick.5

Other Scandinavian Latter-day Saint teenagers were undertaking the same journey. Over the following weeks and months, she might have chatted with Anna Poulson or looked out to sea with Helvig Jenson. If the conditions were decent, she might have played a game with Anne Kraiberg or others. Crucially, she was not alone, and travelling in a group afforded her and others a degree of protection.

The emigrant group was cosmopolitan. The Saints were divided into nine districts, each with a president. The Scandinavians were formed into five districts with Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes leading each other. The captain of the guard and the cook were also Scandinavians. In Liverpool, Johanna and the other Scandinavians had been met by a group of English and Swiss Latter-day Saints who were joining them on their way to Utah.

While Johanna may have had friends to be with, the voyage was not smooth sailing. Stormy conditions caused much sea sickness among the passengers. Still, routines were held. Prayers were offered in the morning and night and on Sundays religious services were held on the ship’s deck. Cold weather and a change of diet further complicated the emigrant’s health. On the 3rd of June, a few weeks at sea, there was an outbreak of smallpox on the ship, but no one died from it. Ten people, however, died during the journey of various causes. However, in happier news, there were also nine marriages and four births. When the ship arrived in New York on the 15th of June 1860, they were detained and no one was allowed to leave until everyone was vaccinated against smallpox. Those who were ill were taken to hospital. After five days of quarantine aboard the ship, a tugboat transported the emigrants to New York along with their luggage and began the next stage of their journey.6

Onwards to Zion - By Rail

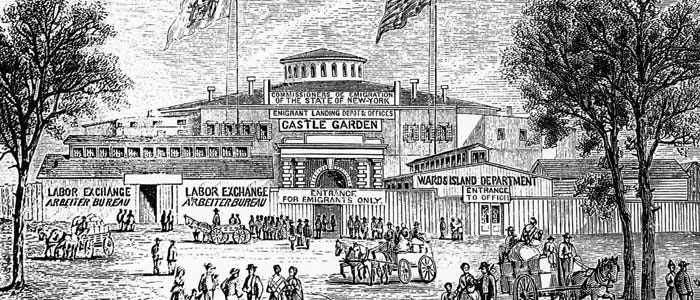

There was no time to wait or play tourists in New York. At Castle Garden the emigrants had been met with members of the Church that had been arranging their onward travel. The next day the emigrants left the city aboard a steamboat which sailed up the Hudson River to Albany, New York. Even though Latter-day Saint emigration from Europe had only begun 20 years earlier there had already been significant developments and technological advances. Railroads now headed further and further west which made the journey to the frontier quicker. George Q. Cannon, who would become an Apostle in August 1860 and later a member of the First Presidency, functioned as the Church’s emigration agent for Johanna’s trip across America and made the arrangements for the emigrants to travel by train. He was an adept administrator and through booking train travel managed to save nearly 300 miles from the journey which was described as a “toilsome and harrassing” stretch. In previous years the stretch from Iowa City to Florence would occupy 15-20 days.

In Albany, Johanna and the others boarded a steam train and set off on an epic journey that would wind through Canada and on to Chicago, Illinois. As they travelled from Albany to Rochester they passed Niagra Falls where the train stopped for seven hours to allow the emigrants to see the waterfalls and the suspension bridge. With some wonder, perhaps, Johanna may have gazed out at the wonder of natural beauty.

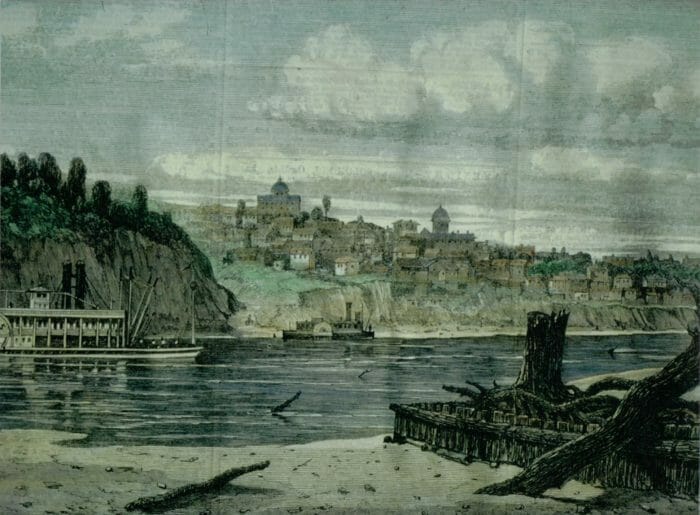

The journey continued onwards and crossed into Canada where the train travelled along the North Shore of Lake Erie to Windsor. It then returned to the United States and arrived in Detroit, Michigan. The next leg of the journey was a train journey from Detroit to Chicago, Illinois. Days were spent on the train watching the scenery pass by. The train journey continued. From Chicago, they travelled to Quincy, Illinois, before crossing the Mississippi River by ferry to Hannibal, Missouri. After arriving in Hannibal they travelled by rail to St. Joseph, Missouri. Again, they boarded a ship and travelled up the Missouri River to Florence, Nebraska, where they rested in some abandoned houses.

There were challenges during these journeys. Occasionally there would be a death and while travelling by train smallpox again broke out, but not in a serious manner.

By Trail

The emigrants had not remained as one group. Some had split off to travel by handcart, but Johanna remained with her mother and the Widerborgs throughout. Their company was the last oxen train to leave that season and was described as one of the largest groups to cross the plains. About 400 people travelled with 72 wagons, 215 oxen, and 77 cows. Their leader was William Budge, but the Scandinavians travelled in a detached group under the leadership of Carl Widerborg, likely for communication reasons. Another group of Scandinavians had set off earlier to cross the plains with handcarts under the leadership of Oscar Stoddard, which would be the last-ever handcart company.

William Budge was a Scottish Latter-day Saint who had served missions around Europe before his emigration. He was a capable and experienced leader who was often looked to by members and other leaders. Various accounts from the 2.5-month journey portray a hard and gruelling experience that would have been eye-opening for Johanna. The following extracts of the journey are from the journal of Danish Latter-day Saint Niels Christensen:

Sunday, July 22. Meeting was held in the camp <in the forenoon>, but we resumed our journey at 3 o'clock in the afternoon and traveled for 6 hours. We passed through a part of the country which was infected with numerous insects and the water was very poor.

Wednesday, July 25. We resumed our journey at 7:30 a.m. and traveled until 3 o'clock p.m., making 16 miles. The day was very warm and both the people and oxen suffered in consequence. We encamped for the night by the Platte River where grass

wasand woodandwas plentiful.Friday, July 27. We continued our journey at 8:30 p.m. The weather in the forenoon was fine, while the afternoon was somewhat stormy. We camped for the night at 4:30 p.m. I was sick and tired during the day. Two Indians came into camp

whoand were treated to food. They were armed with bows and arrows.Tuesday, July 31. We resumed our journey at 8 o'clock a.m. About 1 o'clock p.m. a fearful storm accompanied

with<by> thunder and lightning came up which made travel very unpleasant. The downfall was so plentiful that we could scarcely move because of the water; one wagon belonging to the English emigrants broke. We camped for the night at 3 p.m. Soon afterwards the weather cleared up. About this time the wife of Ola Gaarder from Norway gave birth to a son. We enjoyed a good nights rest not being molested by mosquitoes.Wednesday, Aug. 8. Resumed our journey at 6 o'clock a.m. The roads were quite muddy, owing to the recent rains, and the water had cut several deep channels across the road. A number of Indians on horseback came to the camp wanting something to eat. We traveled during the day 22 miles when we camped after dark. During the day we were annoyed by the grasshoppers which seemed to literally cover the earth.

Saturday, Aug. 11. We resumed our journey at 6 o'clock a.m. and the Indians likewise, but they told us that more Indians would soon

be<put> in their appearance. We had traveled only a short distance when between 1500 and 2000 Indians, consisting of men, women and children were surrounding us. They had with them a number of tents and a multitude of dogs, as well as loose horses. We were very much amused to witness their peculiar mode of travel with their long tent poles and <other equipments>. We gave them some provisions, which, however, did not go far, there being so many of them. They encamped for the night a short distance from the place where we also made our night's encampment in the middle of the afternoon. Most of the day we traveled over sandy roads many of the oxen nearly gave out. We crossed a brook with clear water where we encamped for the night, after traveling 15 miles during the day.Thursday, Aug. 16. We resumed our journey at 6 o'clock a.m., traveled over sandy roads, 8 miles, and camped for noon at 1 o'clock p.m. A meeting was held at which we were ordered to throw away sufficient of our baggage to enable us to travel faster. Between 7 and 8 o'clock today the Indians <surrounded>

tooka sister Madsenand son<who traveled behind the company> with Bro. Widerborg's wife who was lame.and would have<The Indians evidently intended> run away with <Sister Madsen and do violence to her person> them. This caused a great disturbance in the camp. We all grabbed our guns and ran backto fight the Indians but the woman had already escaped<and rescue the woman, but when we reached her, she had already escaped from the savages unhurt>.Three Indians came Bro. Widerborg's wifebut Bro. Widerborg shot her at once.Thursday, Aug. 30. We resumed our journey at 7:15 a.m. Our road at first was level and good, but we soon found ourselves going in among the Black Hills where the climbs were frequently very steep. We did not stop this day for noon, but traveled on till 8 o'clock at night when we encamped on the Platte River, where grass was scarce, having traveled during the day 16 miles. The mountains here are covered with pine and other birch trees.7

Pioneers were witnesses to tragedy, and sometimes victims of it. Niels Christensen, an ardent record keeper, died on the 1st of September 1860 when he was hunting grouse with a friend. His friend had seen birds and cocked his shotgun. After tripping over he stumbled and accidentally shot Niels who died later that night from a shotgun wound to his stomach. Still, Johanna and the others had to continue the journey and get to Utah.

At night the wagons would be drawn into a corral formation and people would camp in the middle. Food was often made up of dried provisions and whatever could be found along the way. Teenagers would be expected to walk and contribute to the company. Streams had to be waded through, cactuses safely navigated, and they would need to put up with mosquitos tormenting them.

Life in Utah

Johanna and her fellow emigrants finally arrived in Salt Lake City on the 5th of October 1860. She later became the plural wife of Ludvig Berg, a Danish Latter-day Saint who became a prominent dentist in Brigham City. She was described as having many friends and associates to who she ministered and that she was a “diligent laborer” in the Relief Society of her ward. She was never able to have children and after Ludvig died in 1908, she and another widow, Louise Berg, became companions and spent their remaining years together.8

Johanna frequently attended the Brigham City Tabernacle and went to the temple for her endowments and to be sealed to her family. In 1920 Johanna died firm in her faith sixty years after she left Scandinavia.

‘Mormon Emigration,’ Preston Chronicle, 26 May 1860, p. 7.

Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint biographical encyclopedia (Salt Lake City, Utah: The Deseret News, 1901), p. 814.

Journal of Niels Christian Christensen, 2 May 1860 - 7 May 1860.

‘Untitled,’ Liverpool Albion, 21 May 1860, p. 20.

Gottlieb Ence, A short sketch of my life, 1840-1918, pp. 8-9, 10, MS 8658, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

Charles F. Jones, Journals, Vol. 2, p. 194; and Vol. 3, pp. 1-4, MS 1679, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

Journal of Niels Christian Christensen, 22 July 1860 - 30 August 1860.

‘Johannah T. Berg Died Last Night,’ Box Elder News-Journal, 30 July 1920, p. 1.