"...Even the Sunday Illustrated...is leaving us alone.”

Antagonism in the British Isles during the 1920s.

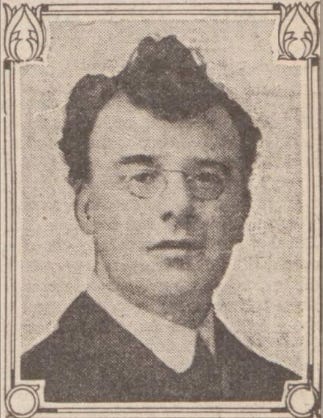

In January 1922, Filson Young, a British journalist and former war correspondent published an article critical of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Both pre- and post-war Britain had been the scene of concerted antagonism against the church with plays, performances, novels, and widespread disinformation being used to create a moral panic about Latter-day Saints.

Filson and his literary contemporaries agitated for Latter-day Saint missionaries to be banned from the country and they would have welcomed the faith’s demise. Of specific interest in the article is the opening paragraph which notes:

“We are having a great deal about the Mormons just now, and it is well that people’s minds should be clear on the subject of this particular bogey.”1

Before long, “Mormons” would become one of the newspaper’s favourite groups to target.

In the same issue there was an article relating a Baptist Pastor’s call for action. The final line concluded in an ominous tone: “No woman who went to Salt Lake City ever came back.”2 Other articles in the same issue also addressed the church.

“We would utter a warning to our family readers to put their womenfolk on guard against specious Mormon missionaries now over here, and who usually call at people’s houses in the quiet hours of the daytime when the head of the family is away at business.”3

The tone and intensity of attention expended on the Church by Filson and other writers for the Sunday Illustrated betrays their desire for sensationalist content at the expense of minority communities. The temerity of Filson and others was borne from a “shoot first, ask questions later” mentality in which a balanced approach to the story was rarely pursued.

Sunday Illustrated

The first issue of Sunday Illustrated was published on Sunday 3 July 1921. The editor of the freshly launched newspaper, Horatio Bottomley, was an independent Member of Parliament who had been an important national figure during the First World War. Horatio was a polarising figure who had a rags-to-riches story. Despite the odds he survived numerous court cases and allegations of fraud and malpractice for many years.

Horatio was best known for his editorship of John Bull, a nationalistic and combative magazine that he used to promote his populist views and helped cement himself into the national political landscape from 1906 to 1920. Eventually, Horatio was forced out of the paper following a failed libel case which is when he launched the Sunday Illustrated.

The first article about Latter-day Saints was published a month after the paper’s founding when a reporter used the subtitle “Pretty Girls Employed as Missionaries.” The article focused on Nottingham where “Lady Missionaries” shared the gospel with others.4 The short article only noted the occurrence without expressing an opinion on the matter, but it soon took an increasingly condescending and aggressive tone towards the faith.

Before long most of the church’s most prominent critics had been featured in the Sunday Illustrated in some way or another. Lulu Loveland Shepard, also known as the “Silver-tongued Orator of the Rockies,” appeared in the paper when she visited England in 1922 as part of an “anti-Mormon campaign.”5 Lulu railed against the missionaries and shared information about temple rites and clothing. Some dubious stories and claims were made that sought to generate outrage and shock the public, which was precisely what the Sunday Illustrated was after.

Some Latter-day Saints, however, tried to push back on the allegations published in the paper. Elder James Western was a 22-year-old missionary in Cardiff who met with a Sunday Illustrated reporter in an interview. The interview was printed in an editorialised manner in which the missionary’s words were matched with comments of disbelief or criticism.

Still, the newspaper began publishing notices seeking information about the missionaries and their efforts to share their faith. Requests for information, such as the following, were seeking to dredge up dirt:

The newspaper, however, was interested in more than just Latter-day Saints with various remedies promoted, and other items advertised for sale. Profitability in a fiscally challenging period brought added complexities for Bottomley and given his financial controversies all means of increasing profits were pursued.

Sensational headlines were utilised to stir interest and to warn of the “menace of Mormonism.” Articles exaggerated the growth of the Church and presented the missionaries and the teachings they shared as dangerous to British society. Taking a page from the American Muckrakers of the time, the Sunday Illustrated brazenly undertook a campaign against the church

Some correspondents also drew comparisons between Latter-day Saints and other groups and communities that were looked down upon by Western society:

Even the debased position held by women in Eastern lands compares favourably with that of the Mormon women, whose homes can be invaded by the Mormon officials at any time. Should she refuse any information about her most intimate life, she is “dealt with” in the temple.

Such stories were typically lacking in details and were unverified. Not that that was important to the paper.

The ‘Nottingham Raid’

The 12 November 1922 turned out to be a rather exciting Sunday if you were attending the Latter-day Saint conference at the city’s Corn Exchange. There was a large crowd gathered for the conference which had attracted leaders such as William A. Morton who had travelled from the Church’s offices in Liverpool. Earlier that year at the previous annual conference it was reported that:

“…the anti-Mormon agitation of the past few months had attracted hundreds of people to the meetings of the Saints, and many were earnestly investigating the doctrines of the Church.”6

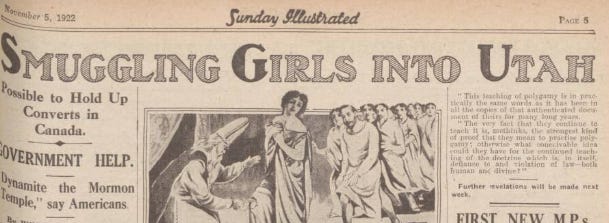

Now, some six months later, they would see whether things had continued in the same direction. The press had been working overtime to whip up public opinion against the Church and the missionaries. On the same day of the conference the Sunday Illustrated advertised the Latter-day Saint conference but “in three paragraphs told as many lies concerning it.”7 It also published a truly sensationalist piece about William Jarman who was a well-known antagonist. Tales of trapped girls being taken to Utah. They published a photograph of him wearing temple clothing which was bound to further inflame tensions.8 An ominous message was included:

If these meetings pass off without incident I shall be surprised. I fancy Nottingham will want to know what these gentle missionaries are doing in the town. and why they are being allowed complete freedom. They think a lot of their women and girls here.

A. Walter Stevenson, a native of Ogden, Utah, was serving as a missionary in the British Mission. He had begun missionary service in May 1921 and by November 1922 he was serving as the Conference clerk. He recorded an account of what happened next in his journal:

"Sunday Illustrated" lies about our Conference. They got special posters out and sell the papers to the people at both ends of Thurland street. Bro. Morton, Elders Geddes, Mathis and I spoke this morning. In the afternoon Elders Pingree & Morton were the speakers. Just as Elder Morton was beginning in walked Rev. Barling and about seven others. They tramped around the hall and the speaker waited for them to take their seats. Barling shouted out: "Go on mister, Never mind us." Bro. Morton said: "This is a licensed hall. We are holding a religious meeting. Gentlemen will keep order, others must." "The religion of Joseph Smith." Bro. Morton said: "Will some one inform an office that we have some work for him." Elder Curtis got up and went out and Barling shut up. Then Bro. Morton preached a sermon right to him. Every seat was taken at the evening meeting. Pres. Jeffery, Elder Smith, & Elder Morton were the speakers. The American consul was there and like the rest of them, enjoyed Bro. Morton immensely. After the meeting Barling shouted a little but was booed out.”9

False accounts of what happened were quickly circulated. But those not belonging to the Church rose to its defence and condemned Barling’s behaviour.10

The next morning Walter and the other missionaries went and had their pictures taken. The newspapers had been taken in by Reverend Barling and various papers refused to print the Elder’s refutations or corrections.11 There were still some issues that prevailed. Elders were sometimes accosted at their street meetings and permission to rent premises for baptisms was constantly being denied. Bad news, hostile news, could have tangible results and it certainly played a role in missionaries being assaulted in different parts of the country.

The Fall of Horatio Bottomley and the End of the Sunday Illustrated

Horatio’s crimes eventually caught up with him and in 1922 he was sentenced to a seven-year prison sentence. In a letter resigning from the House of Commons (to avoid the further disgrace of expulsion), Bottomley bemoaned the hardship of his situation but accepted responsibility for it:

“In the meantime, I must submit to the cruel fate which has overtaken me, and of which to-day's action of the House is by far the most painful part. To me, Sir, expulsion from the House of Commons is a punishment greater and more enduring than any sentence which a Court of Law could decree. It is the very refinement, the apotheosis of torture, and, added to the strain and suffering of prison life, equals any torment any man has ever been called upon to endure. But, Sir, as I have said, I have but myself to blame, and all I can do is to ask hon. Members to judge of me as they knew me. Then perhaps some of them may give a kindly thought to an old colleague, who never played them false, and endeavoured to act up to the best traditions of the House.”

The newspaper did not last long after Bottomley’s incarceration and there was seemingly a tone adjustment. Regardless, in February 1923 mission president and Latter-day Saint Apostle David O. McKay wrote to fellow Apostle Rudger Clawson in which he reported, “Regarding the work here, it is moving along slowly and encouragingly. Even the Sunday Illustrated...is leaving us alone.”12 Slowly, the tide of interest in salacious stories was turning and Latter-day Saints could begin to enjoy somewhat of a break in the constant stream of attacks.

The last issue appeared in print later that year on 25 November 1923, about a year after the ‘Nottingham Raid.’13 It isn’t difficult to imagine the sigh of relief that must have come from Latter-day Saint leaders and missionaries on hearing about the paper’s demise. The Sunday Illustrated, like many other antagonistic papers before it, had been unable to stop the cause of truth professed by the Latter-day Saints.

Filson Young, ‘The Things That Matter,’ Sunday Illustrated, 22 January 1922, p. 7.

‘Mormon Lure,’ Sunday Illustrated, 22 January 1922, p. 2.

‘Beware of Mormons,’ Sunday Illustrated, 22 January 1922, p. 6.

‘New Mormon Move,’ Sunday Illustrated, 21 August 1921, p. 2.

Lulu Loveland Shepard, ‘Twenty-Five Years Among the Mormons,’ Sunday Illustrated, 24 September 1922, p. 5.

Nottingham Conference manuscript history and historical reports, 1852-1951, 23 April 1922, LR 6248 2, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

William A. Morton, ‘Untruthful Statements Refuted,’ The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, Vol. 84, No. 49 (1922), pp. 772-774.

‘Mormon Priest’s Confessions,’ Sunday Illustrated, 12 November 1922, p. 7.

A. Walter Stevenson, diary, vol. 1, 12 November 1922, MSS 1574, bx. 1, fd. 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

William A. Morton, ‘Untruthful Statements Refuted,’ The Latter-day Saints’ Millennial Star, Vol. 84, No. 49 (1922), pp. 772-774.

A. Walter Stevenson, ‘A Nottingham Parson on the Rampage,’ Improvement Era, Vol. 26, No. 3 (1923), pp. 290-291.

Francis M. Gibbons, David O. McKay: Apostle to the World, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1986), p. 125.

‘Sunday Illustrated,’ Daily Mirror, 30 November 1923, p. 14.