Gold Diggers

New records relating to a Latter-day Saint grave robbing scandal

In February 1862 a dark cloud hung over Salt Lake City’s courthouse as hundreds of people entered, looking for their loved one’s possessions that had been stolen from graves in the city’s cemetery.1 Burial clothes from the graves of hundreds of men, women, and children of all ages were laid out on a fifty-foot table for loved ones to inspect and claim. In the home of a nearby grave digger, the police had uncovered a grizzly case of grave robbery with the property overflowing with the clothes and belongings of the dead.

The gravedigger had defiled the graves of their loved ones by digging them up, stealing their clothes, and taking the coffins to use as firewood for his home leaving the corpse naked in the mud to rot. News of graves being defiled in their resting place caused a wave of horror to sweep over the city which rippled around the world.2

As with many sensational stories set in the nineteenth century there have been multiple retellings of this story, including an independent full-length film, many of which have taken liberties with central facts or have failed to follow the data correctly. The notable absence of many details from official records has led to seriously divergent accounts. What follows is a carefully composed version of the story drawing on the best available sources, including some previously unused ones.

John Baptist & the Gold Diggers’ Branch

John Baptist (variously spelled Jean Baptiste or John Baptiste) may have been of French heritage, but he was born on 7 November 1814 in Venice, in present-day Italy. The city-state of Venice had been captured and fought over multiple times. At the time of John’s birth, France controlled the city but they were in the process of handing it to the Austrian Empire, which was completed the following year. On account of the timing of his birth and the Frankic nature of his name, it is not implausible that he might have been born to parents with some connection or involvement with the French military.

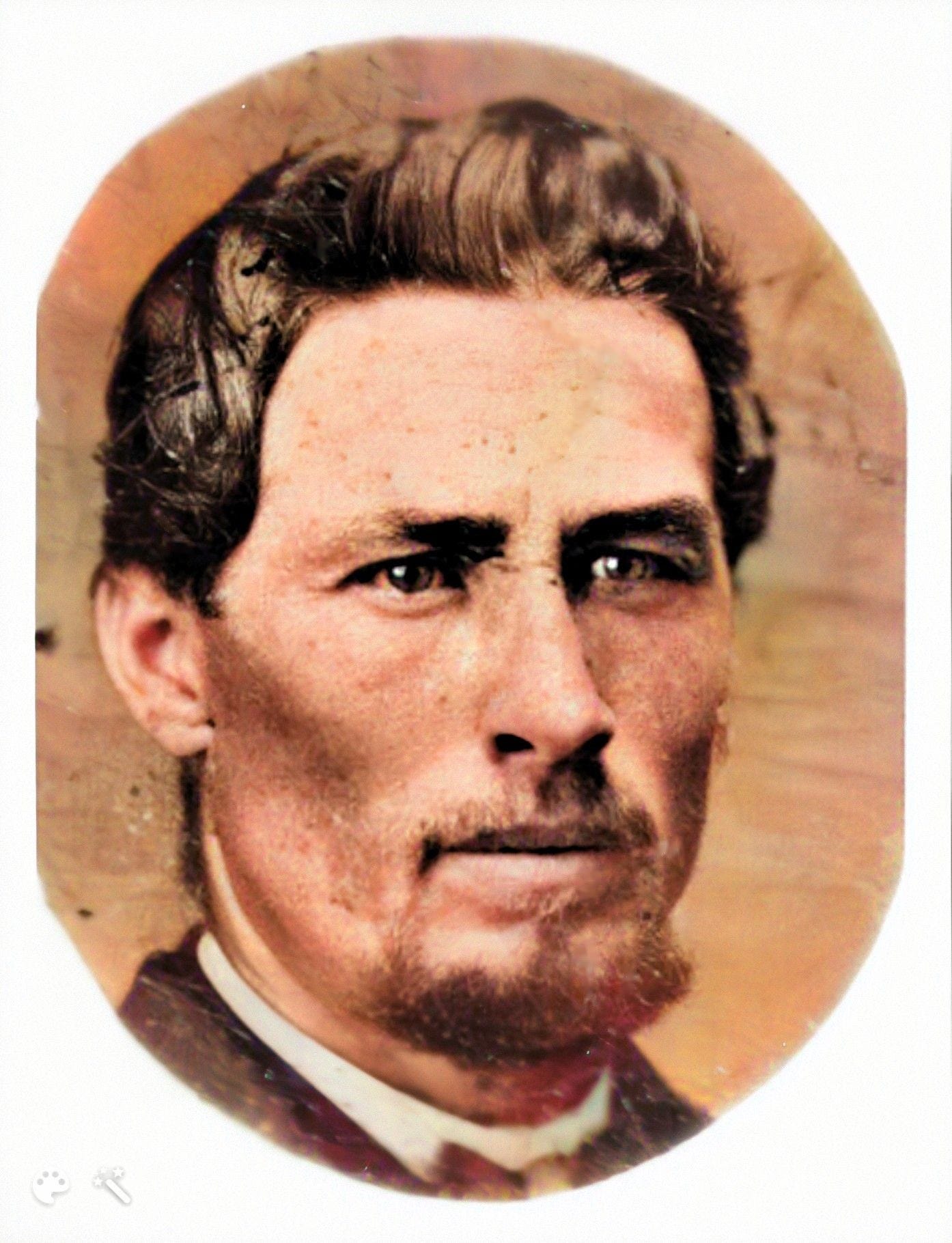

Described as a “dark, handsome man" with brown eyes and curly hair” John left Europe at some point and made his way to Australia.3 In the 1850s he settled in the boomtown of Castlemaine set in the goldfields of Victoria, Australia. People from across the world were drawn to the area looking to make their fortune.4 Castlemaine had sprung up following a gold rush with many residents residing in tents.

The first congregation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints established in the Australian province of Victoria was in Bendigo in September 1853. On account of the extensive gold mining in the area it was called the Gold Diggers’ branch, and the following year there were branches formed in Castlemaine and Kyneton.5 Some of the members were converted in Australia and others were Latter-day Saints who had gone there to make some money.6 John seems to have put his hands to many things including some mining, making and selling clothing, and by any other means.7

In due course, John was baptised a Latter-day Saint by William Cooke, an English-born recent convert and newly called missionary. William had emigrated to the United States and lived in Iowa for a number of years before travelling to Australia in 1852. On the way to Australia to make some money he had left his family in Salt Lake City, despite the fact they were not Latter-day Saints, but it wasn’t long before his wife and two of his children had joined the Church.8 Soon after his arrival, however, he became a Latter-day Saint and before long he was ordained an Elder and appointed to preach the gospel.9

In June 1853 William was set apart as a missionary to work in the gold mining district of Victoria. After meeting success he became the first president of the Bendigo branch, which was at the centre of the gold rush and boom town economy.10 These were areas that had sprung up overnight attracting thousands of people and were particularly dark and depressing environments to preach in. Later that year William was identified as a ‘Travelling Elder’ and it seems probable that it was around this time that he baptised John.11

John had been raised in the Catholic faith but had wandered between faiths spending time as an Anglican and then as a Methodist. He was immediately captivated by the missionaries and the gospel’s message. In Castlemaine, he had built a 60-foot by 35-foot wooden chapel, which he soon showed to the missionaries:

Beloved Brethren, you shall have that to preach in. It is my own property, I have built it with my own hands and at my own expense. I have had one end of the meeting house partitioned off to live in.12

He subsequently allowed the small branch to meet in his chapel and for missionaries to preach there. By at least 1854, the local Wesleyan minister publicly announced that John Baptist was ‘not authorised to receive subscriptions.’13 He had clearly left the Methodist fold and cast his lot with the Saints. In October 1855 the Bendigo Advertiser noted that ‘a placard was posted throughout the town of Castlemaine, announcing that a meeting of the “Latter-day Saints” would take place on every Sunday at the Mormon Chapel in that town.’14 It isn't clear if that chapel was John's or another. In March 1855 John put an advertisement in the local newspaper stating:

To Religious Bodies, Schoolmasters & others. For sale, cheap.-The spacious and comfortable building, having red doors on the Flat, opposite the Camp. Apply to John Baptist.15

The advertisement and inferred sale that followed were spurred by John’s desire to emigrate to North America, which remained an important theological belief for Latter-day Saints. He may have sold it to the Church, to a member, or to another group, but the Saints in Castlemaine remained active despite a portion of them emigrating to the United States of America.

In October 1854 the Australasian Mission Presidency published an article that called on the Australian Saints to ‘…prepare to flee to Zion. Let all whose circumstances will permit commence to arrange their affairs, so that they may be ready to go in the next company, which will leave about April next. Out counsel is that all who can do so, should gather up at that time;-let the Saints obey this counsel and they shall be blessed.’16 John left Australia in April 1855 and William Cooke followed a year later in May 1856.17

John arrived in California and settled there for a time before eventually moving to Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1857. Newly discovered court papers show that in Utah he met and married Elizabeth Taylor in April 1858, but the marriage was unhappy and short-lived. He had misrepresented his financial position to her and she soon discovered that he was not a man of his word. Elizabeth filed a divorce petition later that year and the divorce was granted on the 25th of December 1858. Court records indicate that '…it was fully made to appear that the said parties could not live together in peace + union.’ It was noted that Elizabeth found him too difficult to live with ‘owing to the abuse which she has received from him.’18

Sometime at the end of 1858 or early 1859, John secured employment as a grave digger for the Salt Lake City Cemetery. He lived nearby in modest circumstances and was by all accounts an active and committed member of the Church. In March 1861 he was re-baptised a member of the Church, as was common at the time. In November 1861 he re-married, this time to a recently arrived English Latter-day Saint who had experienced considerable difficulties up to this point in her life. But at what was supposed to be a happy period for John and Dorothy, everything was about to change.

The Death of Moroni Clawson

Moroni Clawson had been raised a Latter-day Saint but at a young age he fell in with a bad crowd which led to him being involved in criminal activities. In due course, he was excommunicated from the Church for his lawlessness. In January 1862, after a string of altercations with the law he was shot and killed while trying to escape from the police.

Because Moroni’s body initially went unclaimed he was buried in Salt Lake City’s potter’s field. Henry Heath, a Salt Lake City policeman paid for Moroni’s body to be dressed before burial as he had buried his eldest daughter, Sarah, less than a year earlier. A few weeks later, on 27 January 1862, the family discovered where Moroni had been buried and received permission to exhume him and reinter him in another cemetery. When digging up the body they found that he was face down and naked. The family was furious with the revelation and Henry began an investigation into the crime.19

The Investigation

On Monday the 27th of January 1862, police officers Henry Heath and Albert Dewey along with two other men arrived at the home of John and Dorothy Baptist. John was not present, but inside the home, the police officers discovered ‘a large quantity of burial clothes’ and other materials, including approximately sixty pairs of children’s shoes. Given Henry had only lost his daughter in April 1861 he became enraged at the idea that John might have desecrated her grave. Henry made his way to the cemetery and confronted John, choking him into making a confession. John spilled the beans and admitted to having robbed a dozen or so graves, but it became quickly apparent that John’s crimes were far more extensive.

When news broke out there was outrage and John was held in the County Jail for his own safety. According to George Q. Cannon, who had met John when he lived in California, his first American graverobbing victim was none other than William Cooke, the local missionary who had helped start missionary work in the gold mining region of Victoria, Australia. After returning to his family in Utah, William began working as a night jailer in the Salt Lake City Jail. A year later, on 15 October 1858, while preventing two men from releasing a prisoner William was shot in the leg. Several days later he died and was buried in the Salt Lake City cemetery. John then robbed his grave and continued with his surreptitious crimes until January 1862.20

…a man, professing to be a Saint and to believe as we do, who would be guilty of robbing the bodies of his deceased brethren and sisters to gratify his devilish cupidity and avarice, when the kind and provident care of their friends had clothed them for ressurrection according to order, would not hesitate to murder if he thought he could make anything by it and not be discovered.

The subsequent investigation revealed that he had begun graverobbing during his time in Castlemaine and that his activities were part of the way that he was able to pay for his chapel.21

Exile

Given the sensitive nature of the crime, there were people who were keen to hurt or even kill John. Elias Smith was the judge who dealt with the crime pulled John out of the jail to question him on 1 February 1862.22 The lack of legal papers raises the question of what due and legal process was followed, but John made some statements concerning how he became involved in grave robbery and confessed his involvement. According to Smith, 'he [John] had robbed many graves, but how many he could not or would not tell.'

Perhaps fearing for his life, John vastly understated the extent of his crimes. Yet the incident generated a furore that caused Brigham Young, president of the Church, to deliver a sermon addressing John’s case. President Young stated that rather than putting him to death that it would be better to ‘make him a fugitive and a vagabond upon the earth.’23

It is reasonable to assume that people took note of the religious leader’s instructions and he was initially taken to Antelope Island where John’s forehead was tattooed with the words ‘Grave Robber.’24 Soon after he was taken to Fremont Island by Henry and Daniel Miller where he was to live alone among their livestock and survive on supplies they brought every few weeks. The water was much deeper and escape was considered to be much more unlikely.

Legacy

There is no consensus on what happened to John other than he did not die on Fremont Island itself. There is some evidence that John managed to escape to the mainland. First, his body was never discovered, which would suggest that either intentionally or unintentionally he left the island. Second, an account exists that notes that three weeks after leaving John on Fremont Island Henry and Daniel Miller, who had transported him there, returned and found him in good spirits. Three more weeks, however, there was no trace of him. The Miller brothers found the small shack broken with the roof and part of the sides of the shack removed. The account erroneously refers to a slaughtered cow that had been killed and the hide cut into strips, however, the Millers only kept sheep on the island, which throws the whole account into question.25 Regardless of what had happened, however, he was gone. Some believe he made it to the shore while others think he drowned. It is unlikely that we will ever truly know.

Some tales, including those retold by Henry Heath, talk of John making it to shore and travelling to Montana and then on to California. That might be true, but we will probably never know what became of him.

Henry Miller left Salt Lake City in May 1862 to serve a mission for the Church. The prospect of indefinitely bringing supplies to John must have quickly lost its appeal for Henry and Daniel. But what if they had permitted him to leave the island? Or perhaps they gave him a ride to the mainland with the instruction to never return to Utah. As I was researching the story I came across one possibility, let me share it with you.

Fool’s Gold

Australia had been John’s home for a number of years and he had made something for himself there. He sold his property and possessions before leaving for America, but where better to return to following his arrest and the subsequent public shaming in America? The Sydney Mail records a death notice for a John Baptist who was a native of Austria and that he died on 5 May 1874 in Gladesville Asylum in Sydney at the age of 60. These details match exactly with the known John Baptist, and would be the correct age at that point.

A year earlier, in 1873, there was another sixty-year-old John Baptist also from Austria who died in Dunolly, near Sydney. Clearly, the 1870s was not a good time to be a sixty-year-old man born in Austria with the name John Baptist. It was exciting to think I might have found the right John Baptist, but an earlier directory indicates a man called John Baptist living in Miller’s Point in 1858, which was certainly not the right John. It seems that despite the similarities the find was a dud, a bizarre fluke, or perhaps a form of fool’s gold for historians.

John Baptist, the Salt Lake City grave robber, could have done all of the things that Henry Heath noted, namely that he went up to Montana and then to California. Given that he had lived for some time in California it would make sense that he might have made his way back there. A return to Australia is not out of the question, but as you saw a promising match fizzled out as more research was conducted, fool’s gold, as it were. For now, the final resting place of John Baptist remains a mystery.

‘Shocking Desecration of the Dead,’ Heywood Advertiser, 22 March 1862, p. 2.

‘Robber of the Dead,’ Deseret Evening News, 27 May 1893, p. 8.

Description of John Baptist by Joseph L. Jameson, available on FamilySearch.

Burr Frost, missionary journal, 24 July 1853, MS 1502, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

Burr Frost, missionary journal, 18 September 1853, MS 1502, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

Australasian Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1840-1897, 7 September 1852, vol. 1, pt. 1, LR 10870 2, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

‘Advertisements,’ Mount Alexander Mail, 27 October 1854, p. 5.

Barbara J. Hewett, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints: a history of members and missionaries in the Bendigo Area, 1852-2010 (n.p.), p. 13; and Burr Frost, journal, 21 June 1853, MS 1502, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

‘The Half-Yearly conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,’ The Zion’s Watchman, Vol. 1, Nos. 20-21 (1854), p. 156.

Australasian Mission Manuscript History and Historical Reports, 1840-1897, 28 September 1853, vol. 1, pt. 1, LR 10870 2, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL; ‘Minutes of the Annual Conference of the Australasian Mission of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,’ The Zion’s Watchman, Vol. 1, Nos. 12-13 (1854), p. 93; and Burr Frost, missionary journal, 26 June 1853, MS 1502, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

‘The Half-Yearly conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,’ The Zion’s Watchman, Vol. 1, Nos. 20-21 (1854), p. 155.

See the diary of Frederick William Hurst, 1854-1855, pt. 4, available at: https://joyceholt.com/FWHurst/part04.html

‘Advertisements,’ Mount Alexander Mail, 6 October 1854, p. 5; and ‘Advertisements,’ Mount Alexander Mail, 13 October 1854, p. 5.

‘Hotels and Coaches,’ Bendigo Advertiser, 20 October 1855, p. 2.

‘Advertisements,’ Mount Alexander Mail, 16 March 1855, p. 3.

Augustus Farnham, Joseph W. Fleming, and Burr Frost, ‘An Epistle of the Presidency of the Australian Mission,’ The Zion’s Watchman, Vol. 1, Nos. 20-21 (1854), p. 154. In the same issue of The Zion’s Watchman it was reported that Elder William Cooke would accompany Elder Augustus Farnham to New Zealand to preach the gospel there, see ‘The Half-Yearly conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,’ The Zion’s Watchman, Vol. 1, Nos. 20-21 (1854), p. 159. ‘The Flight of the Mormons,’ The Argus, 27 April 1855, p. 6.

John Baptiste left Melbourne, Australia, on the 27th of April 1855 with the Burr Frost company. Despite issues with the seaworthiness of the original vessel and some detours, the Saints arrived in San Francisco, California, arriving on the 5th of July 1855. William Cooke emigrated with the Augustus Farnham company onboard the Jenny Ford, which left Sydney, Australia, on the 28th of May 1856 and arrived in San Pedro, California, on the 15th of August 1856.

Civil and criminal case files, Utah, State Archives Records, 1848-2001, FamilySearch available at: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-G1RF-HDG?cc=2001084&wc=M6H1-668%3A284658101%2C284678401, [date accessed: 20 January 2023], Series 373, bx. 5, fd. 45, State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA.

Neil R. Clawson, ed., ‘A History of Moroni Clawson,’ (n.p.), p. 8.

George Q. Cannon, journal, 11 March 1862, available at: https://www.churchhistorianspress.org/george-q-cannon/1860s/1862/03-1862?lang=eng, [date accessed: 20 January 2023].

Hewett, a history of members and missionaries in the Bendigo Area, p. 23.

Elias Smith, journal, 27 January 1862, MS 1319, bx. 1, fd. 5, CHL.

G. D. Watt, ‘Remarks by President Brigham Young,’ Deseret News, 26 March 1862, p. 1.

‘A Gruesome Tale,’ Salt Lake Herald Republican, 2 April 1893, p. 8.

Henry W. Miller, diary, Spring of 1862, MS 1888, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

What a morbid hobby!