Megatherium Cuvieri

and the birth and death of the Deseret Museum

Museum and Menagerie

In 1869, John W. Young a son of Brigham Young, established a venture to collect and advertise the history and resources of Utah. The first curator of the museum, Gugliemo Sangiovanni, was a British-born convert to the Church who had recently returned from a mission in Europe. During his mission to Italy, he visited the 1867 Paris Exposition with fellow missionary John W. Young. Back in Utah, they worked together to establish a ‘Museum and Menagerie’ for the benefit of the people of Utah and as an attraction for those visiting the territory.

Local residents donated items to the collection and travelling exhibitions made their own stops to showcase bizarre and rare objects at the ‘Museum and Menagerie’. In 1870, shortly after opening, a travelling exhibition visited the museum to display the skulls of four murderers and invite viewers to ‘decide as to the truth of phrenology as a science’.1

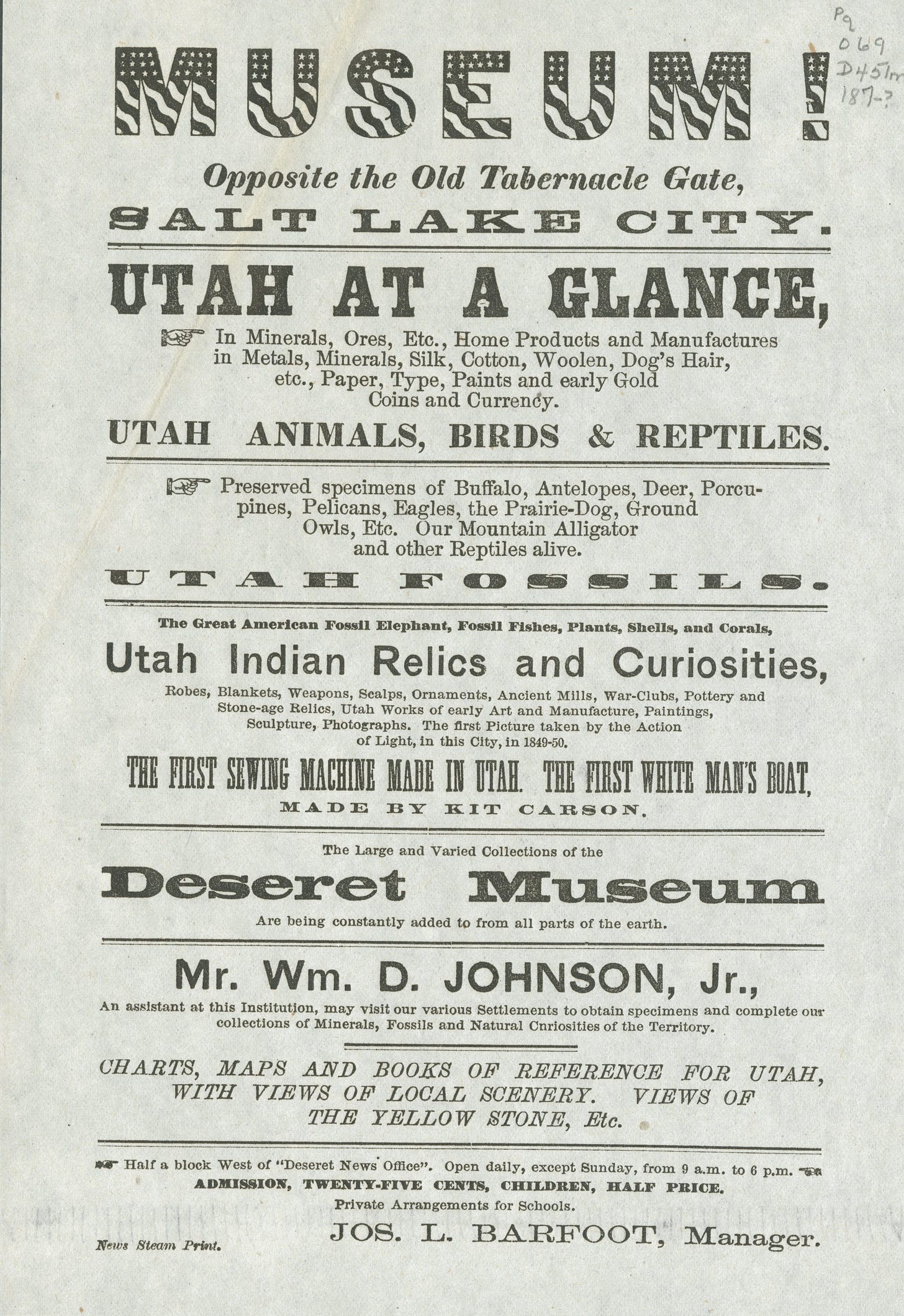

Sangiovanni began selling portable museums which included a collection of minerals, woods, and other items from Utah. It was called ‘Utah at a Glance’, and the miniature museum was sold to tourists who could carry a piece of Utah with them.2

The two men based their operations in a two roomed adobe house on South Temple Street that had originally been built by John’s father. Live animals, objects of fascination, and items from around Utah were made available for interested persons to view. In 1871 Sangiovanni left the Salt Lake City Museum and Menagerie to pursue other ventures. Undeterred, John Young worked with others and the enterprise continued.

In 1878, the facility became a possession of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and was then directly administered by it when it became too expensive for John to absorb the costs of maintaining.3 In 1885 the Church placed the museum into the custody of the Salt Lake Literary and Scientific Association around which time it had become known as “Deseret Museum”.

In 1890 the ground the building was on was sold and the museum moved its collection to the Templeton building and opened its doors again in January 1891. At this point, James E. Talmage, a British geologist and Church leader assumed the directorship of the museum. Over the subsequent years, the museum was moved to several locations. In July 1903, however, the museum was closed for seven years. The collections were placed in storage and while acquisition work continued the enterprise was closed to the public.4

In July 1911 the museum once again opened to the public this time in another new venue, the Vermont.5 A small admission fee was initially charged but eventually this was dropped and it became free to enter. In 1911 Sterling Talmage became the curator of the museum. Guglielmo Sangiovanni eventually returned to work as an assistant to Sterling years more than forty years after leaving the original venture. In the late 1910s, there was an average of 4,000 visitors per month.6

Curator Joseph L. Barfoot noted that:

“The Deseret Museum contains almost everything that is found in Utah, which is of interest to the tourist or visitor, seeking reliable information respecting the minerals, ores and natural resources of the Rocky Mountains.”7

Megatherium Cuvieri

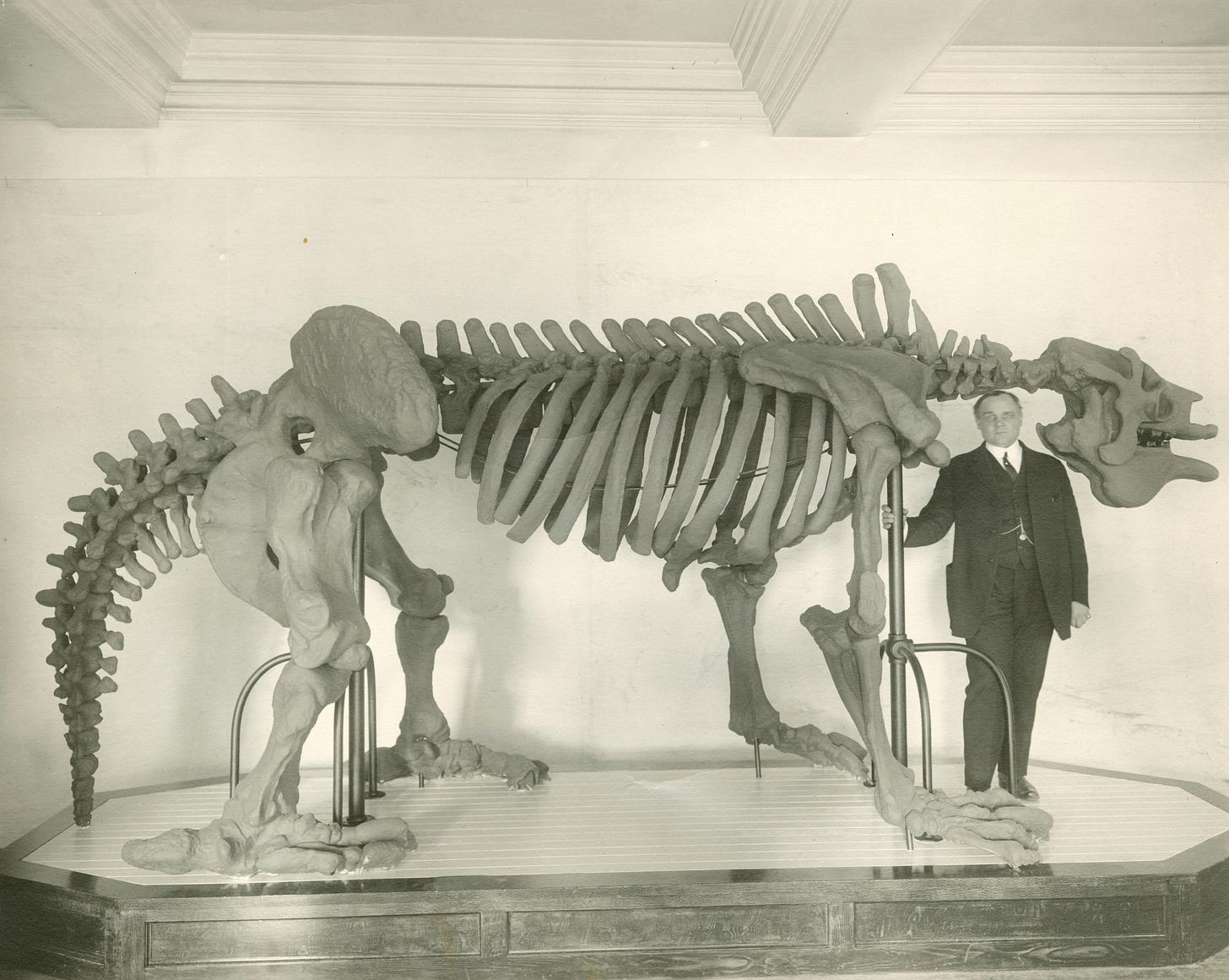

In 1789, a ‘colossal’ skeleton was discovered on a riverbank near Buenos Aires in what was then the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata, which is present-day Argentina. Other specimens were found in other South American locations in the ensuing years.8 Georges Cuvier, a prominent French naturalist, noted the similarities between the skeletal remains and fossils with that of a sloth and coined the term megatherium which was the amalgam of two Greek words meaning “great beast”.9 The skeletons revealed a skull some thirty-one inches long with teeth up to ten inches long. The hip joint of the beast was found to weigh 660 pounds. This was a large, heavy, and slow-moving mammal. It was essentially an elephant-sized sloth. The herbivore was indigenous to South America and was theorised to function either in isolation or in small groups.

In February 1912 it was announced that James E. Talmage had secured an agreement to exhibit the replica skeleton of a megatherium cuvieri that had been discovered in South America between 1831 and 1838. The exhibit was crafted from models of the original bones and was arranged by an exchange with the Kent Museum of Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The skeleton was described as being eighteen feet long and seven feet high. The copy was anticipated to be “one of the most treasured possessions of the Deseret Museum.10 For your interest you can find a photograph of James E. Talmage posing next to the skeleton model below.

In 1911 James Talmage discovered and unearthed bones of a mammoth near Bear Lake which he secured for the Deseret Museum. The skeleton, it was claimed, was “one of the most valuable of its kind that has been unearthed in this country.” Donations of all kinds were accepted to enrich the collection available to local residents and tourists alike.11

The museum was successful in assembling a wide range of artefacts, items, and fauna. Models of flesh-eating plants, mounted animals, fossils, rare minerals, relics from indigenous persons, mummified bodies, and more were put on display for people to view six days a week from 9.30 am-4.30 pm.

James Talmage worked to effectively network the museum and ensured it became part of the Museums Association and the American Association of Museums.12 But in 1919 the museum was broken into different divisions and items were diverted to different entities such as the L.D.S Church Museum.

In his announcement of the closing of the museum, James Talmage noted that:

“Each of the offshoots is set in fertile soil with favorable atmosphere, and it is not too much to hope and expect that each shall surpass the record of the original, but now honorably terminated, Deseret Museum.”13

‘Still Adding,’ Deseret Evening News, 6 January 1870, p. 3.

‘Portable Museum,’ Salt Lake Herald Republican, 20 May 1871, p. 3.

‘The Deseret Museum,’ Deseret News, 18 September 1878, p. 8.

James E. Talmage, ‘The Deseret Museum,’ Improvement Era, Vol. 14, No. 11 (1911), pp. 953-982.

‘New Quarters for Deseret Museum,’ Salt Lake Tribune, 10 August 1910, p. 4.

James E. Talmage, ‘The Passing of the Deseret Museum,’ Deseret Museum Bulletin, 15 February 1919, pp. 1-4.

Joseph L. Barfoot, ‘Handbook Guide to the Salt Lake Museum,’ 1881, 069.5 D451h 1881, bx. 1, fd. 1, CHL.

Henry A. Ward, Notice of the Megatherium Cuvieri, the Giant Fossil Ground-Sloth of South America (n.p., 1864), p. 5.

Ibid, p. 6.

‘Building Model of a Megatherium,’ Salt Lake Telegram, 23 February 1912, p. 10.

‘Museum Given Coins,’ Salt Lake Telegram, 13 April 1916, p. 8; ‘Bomb in Museum!,’ Salt Lake Herald-Republican, 29 August 1913, p. 11; ‘Tarantula for Museum',’ Salt Lake Telegram, 22 August 1917, p. 8; and ‘Freak Apple Seen,’ Salt Lake Telegram, 13 December 1917, p. 6.

‘The Deseret Museum,’ Salt Lake Tribune, 1 January 1896, p. 24.

Talmage, ‘The Passing of the Deseret Museum,’ p. 4.