Spanish Flu in the Society Islands

When mission leaders learn about a disaster

Mission leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints often have to juggle multiple competing pressures. Issues can emerge in various places: among members, missionaries, congregations, local officials, Church leaders, and so on. Sometimes, however, these issues are outside of the control of mission leaders and instead they have to try and chart a course through a crisis as best as they can. The Spanish Flu pandemic broke out and spread globally at the close of the First World War leading to millions of deaths. How people learned about the pandemic, however, varied quite considerably. The following story is about how two mission leaders in the Pacific learned of the disaster and their account of what happened in the opening stages of the pandemic as it ravaged Tahiti.

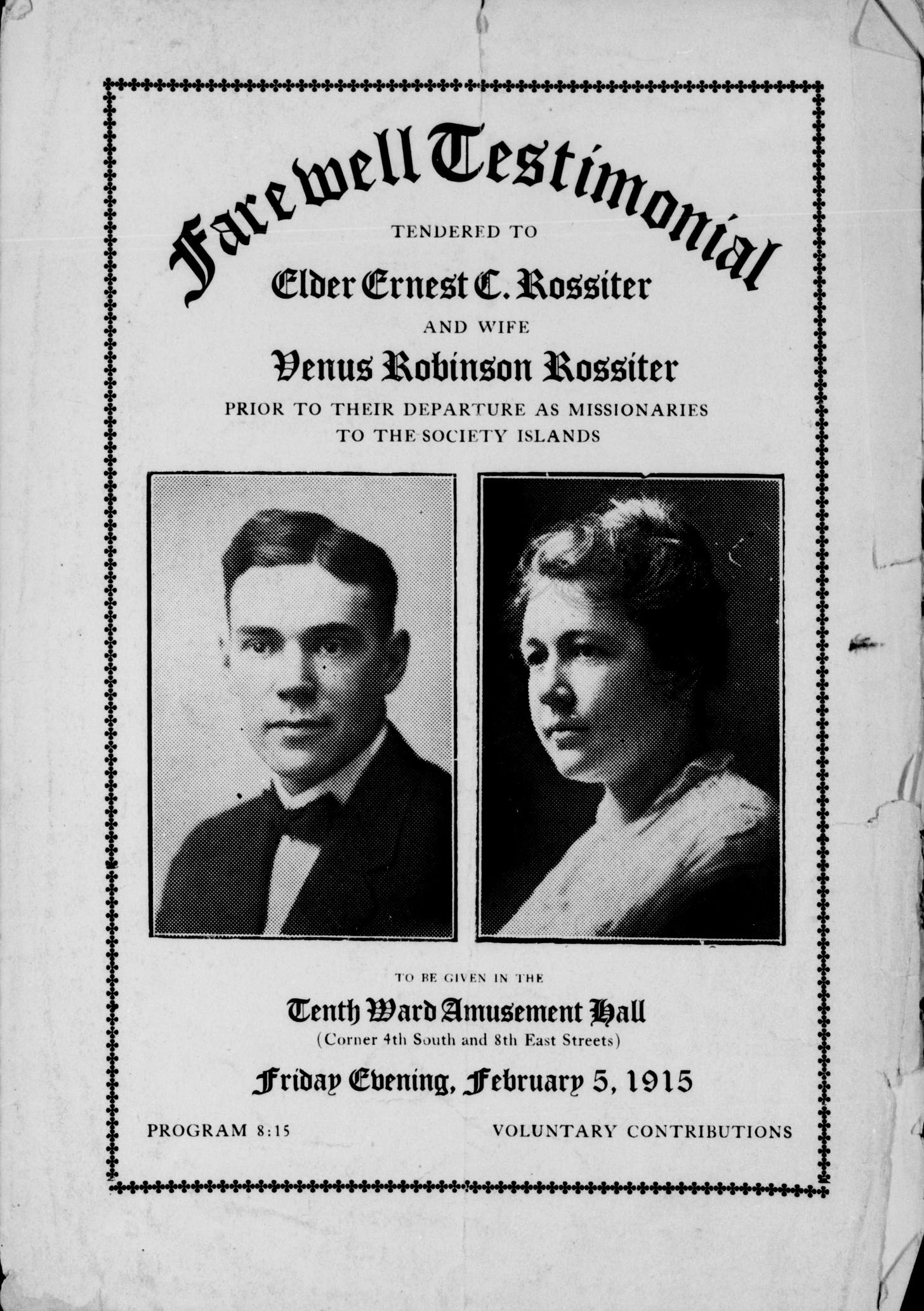

Ernest and Venus Rossiter

In the autumn of 1914, amidst the backdrop of The Great War, Ernest and Venus Rossiter were called to serve as mission president and wife over the Society Islands Mission based in Papeete, Tahiti. This volcanic archipelago with scattered communities set to a jungle backdrop was a far cry from the Wasatch Front, but it was home to approximately 1,300 Latter-day Saints. The history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Pacific dates back to the early decades of the faith.1

Venus Robinson married Ernest Rossiter on June 28, 1911, when she was just twenty years old. Born and raised in Salt Lake City, Utah, Venus came from a family of devout Latter-day Saints, with an English father and an American mother. Ernest, nine years her senior, had previously served as a missionary in the Netherlands Mission from 1905 to 1907.

During their time in the Society Islands, Venus and Ernest faced major events that tested their faith and resolve. The outbreak of the First World War, the devastating Spanish Flu pandemic, cyclones, earthquakes, and other natural disasters were some of the significant challenges they had to navigate.

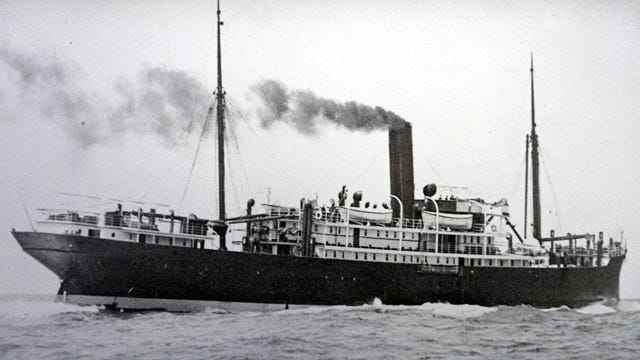

The Spanish Flu pandemic comes to the Pacific

On 16 November 1918, Navua, a ship from San Francisco, United States of America, arrived in Tahiti. A sick passenger and several unwell crew members caused no alarm, but within a week the Spanish Flu was ripping through the Society Islands.2 The next day a young crew member died and by that evening 17 of the 22 crew members reported being ill. It did not take long for the influenza, however, to infect others. Those involved in the quarantine became ill and before long multiple vectors were transmitting the virus across the island. Soon doctors estimated that 90 per cent of people were infected during the pandemic.3

Similar outbreaks happened on other nearby islands. In Western Samoa, 30 per cent of adult men, 22 per cent of women, and 10 per cent of children died from the illness.4 Tonga lost 10 per cent of its population, Fiji 5 per cent, and ultimately 20 per cent of the population of Tahiti died in the pandemic.5 Ultimately, millions of people around the world died from the illness.

When the Navua arrived in Papeete President and Sister Rossiter were on a different island, Hikueru, working and living among the Saints. News reached them of the worldwide pandemic in late November. Over the next few days, the outbreak on Tahiti was kept secret but it was spreading quickly. On 22-23 November armistice celebrations were held in Papeete and other towns which only fueled transmission. On 7 December, the Rossiters left Hikueru and after a nine-day journey arrived at Tahiti and entered into quarantine.

On the evening of December 16, 1918, the Rossiters and their fellow passengers were given heartbreaking news about the Spanish Flu outbreak on Tahiti and neighbouring islands. The devastating illness had already claimed the lives of thousands. The news had a profound impact on the passengers of the ship. Venus describes the passengers and their reactions along ethnic lines. She writes of a group of Chinese passengers who secluded themselves and were fearful of the disease. The Tahitian passengers were upset at the news but expressed the saying “Tei te Atwa” or “It is God’s will.” However, two white passengers reacted differently. They were angry and frustrated, pacing the deck and cursing God. They believed that no God would allow such suffering and misery.

Venus and Ernest were worried about the ongoing development. They retreated to a private area on the boat and prayed to God, expressing their faith in Him and dedicating themselves to His protection and guidance. From the deck of their ship, the Rossiters could already see the impact of the pandemic. The following is an extract from Venus’ journal:

It was a forbiding scene that greeted our gaze the next morning after a sleepless night. Papeete was deserted with no signs of life on the streets excepting the improvised Red Cross truck racing to + from the hospital, and the “death truck” carrying dead bodies to the cemetery from where we could see the thick smoke rising up from the cremating ovens where the bodies of the dead were being burned. A ship was high and dry on the reef, its entire crew having died at sea + it was left to the mercy of the waves.6

The next day Venus and Ernest requested and received permission to land and were set on a row boat and pulled to shore by the port pilot. Upon landing they were given antiseptic masks to cover their faces. Other white passengers in quarantined boats were incredulous at the fact the Rossiters had chosen to land given what was occurring on the island. “Good luck to you, you are more courageous than we,” some of them called out.

Still, the Rossiters felt compelled to land and assist the Saints. Of the decision, Venus recorded:

…we knew that it was our place ashore with our Elders and Saints, and as we were engaged in God’s work and had dedicated ourselves into his keeping we had no fear whatsoever.7

The mission leaders found that five elders had been ill with influenza but had all fully recovered. Another two had escaped illness altogether. The Saints had also generally fared well with only a few passing away. In her journal, Venus relates what she learned about the arrival of the Spanish Flu:

When the disease first broke out the French officials were so terrified that they locked themselves up in their houses and let it run rampant + hadn’t the British + American population taken matters in hand the entire population would have undoubtedly been wiped out. People were dying everywhere, the dead + decaying bodies being found on all the streets in the fields + in the houses, many of them which had to be burned with the dead in them. Two hospitals were established by them where the afflicted were taken + cared for free of charge. Trucks were pressed into service to carry the sick to the hospitals + take the dead to the cemetery where the bodies were cremated. And the city was divided off into sections and American + British residents appointed to take charge of it and care for the sick. Our elders have certainly aquitted themselves with credit by their fearless + untiring work. Some are night nurses in the hospitals, while others are given districts to care for, where they have been going from house to house, night and day, dispersing medicine. Scrubbing out the filthy polluted houses of the helplessly sick, cooking food + feeding it to the patients, careing for orphaned babesand children, bathing the patients, carrying out the dead, digging graves, making coffins, hauling dead to the cemetery, etc. etc. etc. They say the sights + scene they have seen + the things they have had to do could hardly be believed if told they were so terrible…Houses are standing empty on every side where entire families have been taken by the disease. We fortunately haven’t had many of our people die and have been able to save them all being hurled into the furnace + had them properly buried…8

In the following days, weeks, and months the Rossiters, missionaries, and members grappled with the realities of living through a pandemic. Public meetings were banned and death continued to stalk the island. Venus Rossiter’s account of an island beset by death and illness is supported by other accounts:

Tahiti, in the Society Islands (French Polynesia), was also devastated, losing one-seventh of its 4,500 inhabitants between November 25 and December 10, 1918. Among the native population morbidity was nearly two-thirds. The death toll was so high that proper burials were not possible. Instead, the streets of Tahiti were full of trucks transporting the dead to mass cremation sites.9

In time the pandemic abated and life gradually returned to normal. The Rossiters continued serving until their release in 1919. Today there are almost 30,000 Latter-day Saints across almost 100 congregations. The Rossiters loved and cared for their missionaries and the members of the Society Islands Mission. The hardships they faced no doubt stayed with them for a long time, but their calm and steady leadership helped the Church on Tahiti and other islands to remain strong during a period of tremendous upheaval.

Arnold K. Garr, ‘Latter-day Saints in Tubai, French Polynesia, Yesterday and Today,’ Reid L. Neilson, Steven C. Harper, Craig K. Manscill, and Mary Jane Woodger, eds., Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint Church History: The Pacific Isles, (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2008), pp. 1–22.

William Matthew Cavert, ‘In the Grip of Calamity: Tahiti and the 1918 Spanish Influenza Pandemic,’ The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 57, No. 1 (2022), pp. 1-20.

Jean-Louis Rallu, ‘L'épidémie de grippe de 1918 aux iles de la Société,’ Population (French Edition), Vol. 35, No. 2 (1980) p. 1085.

Sandra M. Tomkins, ‘The Influenza Epidemic of 1918-19 in Western Samoa,’ The Journal of Pacific History, Vol. 27, No. 2 (1992), p. 181.

Cavert, ‘In the Grip of Calamity,’ p. 6.

Venus R. Rossiter, journal (1918-1919), 16 December 1918, MS 18002, bx. 1, fd. 2, CHL.

Ibid, 17 December 1918.

Ibid

George C. Kohn, ed., Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present (New York, NY: Facts On File, 3rd ed., 2008), p. 363.