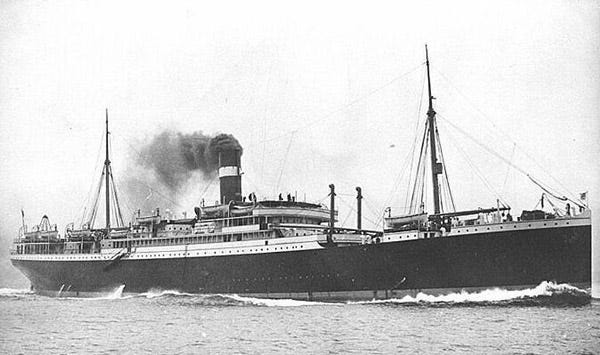

The Hesperian

"May God bless them and preserve them..."

On the evening of 5th September 1915, 12-year-old Joseph Catten was settling down for the night onboard the Hesperian a twin-screw passenger liner sailing from Liverpool, England, to Montreal, Canada. He was accompanied by his older brother, George, and they were emigrating to Salt Lake City to live with family members. The ship had left Liverpool only two days earlier and was carrying passengers, goods, and injured Canadian servicemen.

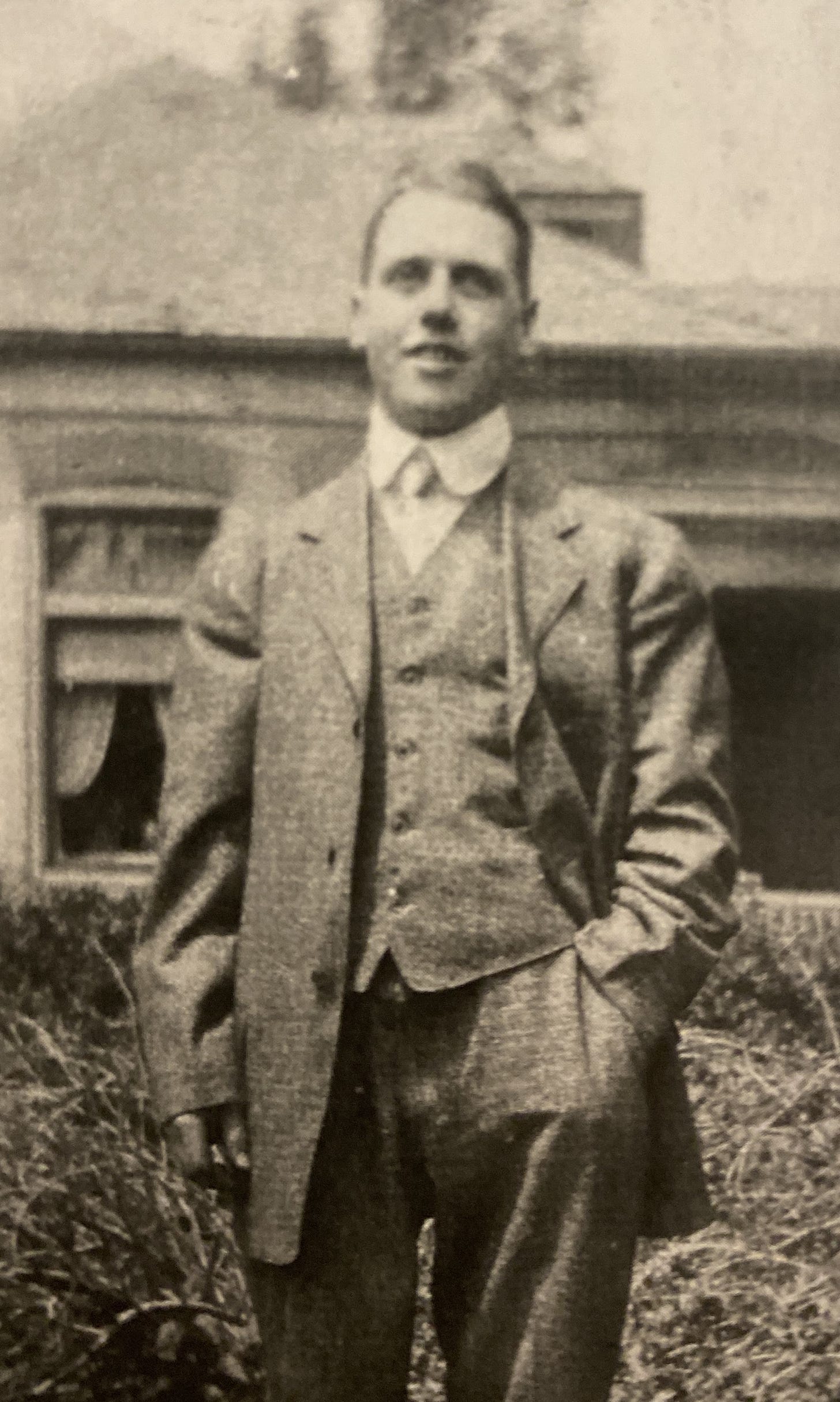

Joseph and George were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and had been born and raised in London, England. The Catten family had joined the Church in 1907 and served faithfully thereafter with their father holding street meetings and their mother serving as a Relief Society President for many years.

There were two other Latter-day Saints aboard the Hesperian, Marie Andersen (57) and her daughter, Maren (28), who were converts to the Church from Denmark. All of Marie’s children who reached adulthood emigrated to North America and she determined to join her daughter Christiane in Magrath, Alberta, Canada.

The Sinking of the Hesperian

In September 1915, war not only stalked the bloody trenches of France but also the dark and mysterious waters of the Atlantic Ocean.1 In the months previous various military and civilian vessels had been attacked and sunk by German submarines, known as U-boats, which had agreed to only attack legitimate military targets. War, however, is complicated and the definition of “legitimate military targets” seems to have been hazy for some. It was further complicated as British merchantmen installed hidden guns to surprise and attack U-boats that might surface and in so doing German officers began undertaking unrestricted submarine warfare.

At 8.30 pm, Joseph and George were sitting on their beds partly dressed and preparing for bed when there was a terrible explosion. The ship shook, rocked, and tilted starboard side before righting itself. Both of them were thrown around the room.

The ship was immediately stopped but it was apparent to the two boys what had happened. The explosion had caused panic among the passengers. The brothers had to work their way through the crowded hallways to make it onto the top deck. On top George realised that he had forgotten their lifejackets and he headed back to retrieve them. Meanwhile, lifeboats were being lowered into the ocean.2

Joseph and George saw a boat being lowered and they clambered onto the rail to jump in but they were told it was too full, so they clambered back onto the deck and searched for another boat. Further along, they found a boat with only three men in it. As it was being lowered the pulleys jammed on one side but the other side continued to lower. George grabbed hold of Joseph and held on tightly to his seat. Another boat, not realising what was going on, was being lowered above them and crashed into their boat which in the panic did not have its plug re-inserted. Suddenly, Joseph and George found themselves in the freezing ocean waters separated from one another.

Terror must have surged through their hearts and minds. Both boys drifted about in their lifejackets in the darkness. Fortunately, both were picked up by other lifeboats.

Joseph was pulled into a lifeboat that was already beyond capacity. There was again no plug installed in the boat with people likely having to continue to bail the water. There was also only one oar and the ocean’s waves would cause people to lift up off their seats as they went over the crest. Another woman was rescued after Joseph and laid across his legs. She was badly injured and died before they could be rescued. Eventually, at 2 a.m., a British sub-chaser came along and rescued Joseph and his fellow survivors. Tears fell as Joseph, overwhelmed by the experience, feared for his brother.

Later that day the two brothers discovered that they had been picked up by the same ship and were joyfully reunited, grateful that the other had made it. After a few days in Ireland, the brothers were taken to Liverpool. There they met with some missionaries and eventually President and Sister Smith who took them shopping to replace some of their belongings.

Joseph recalled the following:

“…we were treated as though we were members of the family. Sister Smith hugged me and took care of us as if we were her own children - which brought tears to my eyes. Sister Smith made quite an impression on me, for she was the same build as my mother and I really appreciated her concern for us. We had supper and also spent the evening with them.”3

After the ordeal, Joseph was hesitant to continue the journey and to sail across the ocean again. Yet George prevailed and after encouraging his brother they decided to try again. After a nine-day trip, they arrived uneventfully in Quebec, Canada, where they continued their journey to Utah. The Andersens also survived the sinking and were rescued. They continued their journey to Canada and also arrived safely.

The Care of Mission Leaders

At the time the British Mission was presided over by Hyrum Mack Smith and Ida Bowman Smith who served as the Mission Relief Society President. Hyrum, the son of Prophet and President Joseph F. Smith, was also an Apostle in the Church and held a great love for the Saints in Europe and harboured hopes that many of them would be able to gather to Utah.

The Smiths were in Ireland when news of the Hesperian reached them and were immediately concerned for the Andersens, who they knew were on the ship. They returned to Liverpool a couple of days later and were soon reunited with them. At the time the Smiths were unaware of the Catten boys. The following diary entries outline the Smiths’ response to the sinking and the steps they took for the Latter-day Saints caught up in it (original spellings preserved).

5 September

This morning we got the news that the Hisperian had been torpedoed but was still afloat. She had been torpedoed after dark Saturday night without warning. Some are reported lost. We have been greatly concerned because our Sisters Anderson were on the ship. We can only hope they are among the survivors.4

6 September

“Report has it that the SS. Hispernian sank this morning at 6.45 a.m. Most of the passengers and crew being saved. About 20 lives are reported lost. No details yet published.5

7 September

We reached Liverpool at 3 p.m. and found all well at home. The survivors of the Hespernian will reach here late this evening. We have word that our sisters are among them. For this we are very gratified.6

8 September

Found the sisters Anderson at the Lord Nelson Hotel this morning. They are feeling very well considering there awful experience. They are bereft of everything. They had retired when the ship was struck had not time to dress. They were taken off in a boat and later picked up by a ship.7

9 September

Ida and Bro Godall went with the younger sister Anderson and purchased them under and outer clothing and fixed them up comfortably. They were exceedingly gratiful. They depart again tomorrow…We received a letter yesterday from a sister Catton of London stating that she had two sons on board the Hisperian and she asked us to look them up and help them if we could. The boys were aged 17 and 11 years. Their names were George and Joseph. Bro Southwick found them. They too had lost every thing and had been given some cheap clothing by the Co. Sister Smith took them down town and fitted them out. Both boys had been thrown in the water but had been rescued. The story of our folks was exciting and pathetic.8

10 September

The ship Corsican sailed to day with our sisters and brethren on board. May God bless them and preserve them from the murderous and savage Germans and take them home in safety.9

That same day, the 10th of September, a cablegram also arrived from the First Presidency explaining that emigrants sailing on belligerent ships had to assume personal responsibility. The notice conflicted Hyrum. He wanted to ensure the safety of the Saints but also to continue the work of gathering the Saints to Zion, which in his estimation was among the Latter-day Saints in North America. News of the sinking angered and frustrated Hyrum who blamed the conflict firmly on the Germans. He expressed a complete abhorrence for the incident which he considered immoral. The Smiths continued to serve the Saints in Europe until August 1916 when they returned home to Utah (uneventfully).

Walther Schwieger

The U-boat commander who sunk the Hesperian was Walther Schiweger, a thirty year old naval officer from Berlin. Just days before the attack on the Hesperian Count Johann Bernstorff, the German Ambassador to the United States assured the United States government that “Liners will not be sunk by our submarines without warning and without safety of the lives of non-combatants, provided that the liners do not try to escape or offer resistance.”10

The sinking came just weeks after the loss of another British passenger liner, the Arabic (which also had a Latter-day Saint missionary onboard), and American officials were becoming irate with German attacks on civilian vessels despite the assurances that they would stop.

In Germany Schwieger returned to base and was treated with disgust and anger for violating the agreement. The Prussian Secret Police arrested Walther and beat him for attacking another passenger liner. German officials first tried to deny involvement in the sinking, but others, such as Ambassador Bernstorff, pointed out that there had been a cannon on the deck of the Hesperian and that as a result it did not fall under their recent agreement.

Schwieger was allowed to resume his commission and continued as a commander on the U-boats until he died on 5 September 1917, almost two years after the attack on the Hesperian. His U-boat hit a British mine off the coast of the Netherlands and was sunk with all lives lost.

War

The Cattens and Andersens escaped death and were fortunate to be rescued. This is not the only story of Latter-day Saints surviving ship wrecks during the First World War. The main takeaway, however, is that Church officials and members continued to love and serve those suffering from the effects of war. Although primary efforts centred on helping members of the church, there were efforts to help people of all backgrounds and circumstances. That is a message that can, should, and does continue today.

J. M. S., ‘Another Liner Torpedoed,’ The Latter-day Saints’ Millenial Star, Vol. 77, No. 37 (1915), pp. 581-583.

George Catten’s account of the sinking of the Hesperian.

Joseph Catten’s account of the sinking of the Hesperian.

Hyrum Mark Smith, mission journal, pp. 76-77, MS 5842, bx. 1, fd. 4, CHL.

Ibid, p. 78.

Ibid, p. 79.

Ibid, pp. 79-80.

Ibid, pp. 80-81.

Ibid, p. 82.

Correspondence between Johann Bernstorff and the Secretary of State, 1 September 1915, 763.72/2084, Office of the Historian, United States Government.