“This will not influence us in the least"

How Latter-day Saints faced hostility in the Eastern United States during The Great War.

It was early in the morning of the 20th of January 1916 and all was quiet in Buck Valley, Pennsylvania. Several hundred men, women, and children lived in the township and all of them were sleeping, well, almost everyone. In the dark of night a person, or persons, was making their way to a building site near the post office. There stood a nearly completed building with a wooden frame and steel tiles on the roof. All that was left to do was the internal plastering.1 Suddenly, an explosion cracked out like a clap of thunder which could be heard twelve miles away.2 Windows rattled and the reverberations passed back and forth across the valley until they faded away. Everyone was now awake.

Bloodhounds were soon called for and set on those who had wreaked havoc on the otherwise peaceful settlement.3 Accounts diverge with some saying the hounds picked up a scent and followed it to a nearby stream, but that the trail grew cold.4 Others claim it led to the middle of a road and then disappeared suggesting a car had collected those involved. Although some people suspected neighbours living just south of the chapel site, the perpetrator or perpetrators got away with the crime.5 An almost completed building had been blown up into atoms with parts being scattered over a large distance.6

The chapel in question was a Latter-day Saint building project and it was about to have been dedicated.7 There had been Latter-day Saints in Buck Valley since the late nineteenth century and by 1916 there was a congregation of about forty members led by local members.8 It was well known that Latter-day Saints were looked down on by their neighbours and the religion was viewed with suspicion. Although they faced hostility, the Saints and missionaries had been working together to build the chapel which had just been destroyed with dynamite. The opposition, it seems, knew no bounds.

Despite the attack, the Saints in Buck Valley led by Johnson Jonathan Hendershot were not deterred by the hostility and remainder firm in their faith.9 They had been waiting twenty years for their own building to meet in and now they would have to be patient a while longer.10

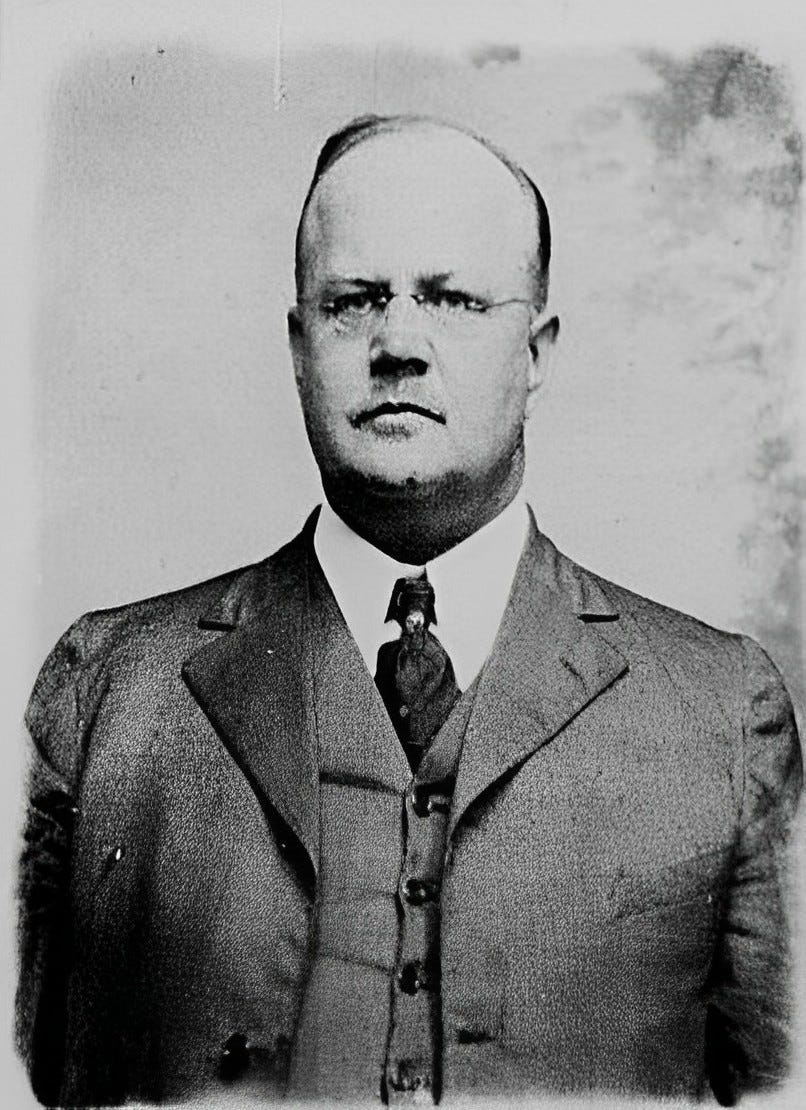

A few days after the attack, mission president Walter P. Monson visited the site. In a report to The First Presidency, he noted that the incident had galvanised support for the Saints and stirred the wrath of local residents that someone would go that far. Forty sticks of dynamite, it was estimated, were used for the act which had shattered the concrete foundations, smashed the oak floor, and caused the roof to fail. It was completely and utterly wrecked.11 The ruins were described as being akin to a “toothpick factory rather than a building.”12

The Crisis Widens

Despite the destruction of the Buck Valley chapel and the ongoing opposition to the Church, the work of proclaiming the gospel continued. Missionaries across the Eastern States Mission worked with local Saints to bring in new members. This growth, against the odds, meant they needed better worship accommodation.

A new mission headquarters and chapel were proposed and approved for Brooklyn, New York, where the mission president was based. News reached the public and just as in Buck Valley there were people who vehemently opposed the church building new facilities. A few months later, in the summer of 1916, Walter P. Monson, president of the Eastern States Mission, received several ominous letters in the post.13 As one of them read:

“Monson you had better not build a Mormon temple in New York. If you do it will be dynamited, and I hope you are in it at the time.”14

Yet Walter was undeterred and he pushed ahead with the construction.

In the early twentieth century, there was an enormous swell of interest in dynamite. During that time it was used to target the Saints across the United States. In 1901 a Sunday School in Vernal, Utah, had its organ blown up by persons unknown.

In 1908 a chapel was blown up in Montecall, Georgia, with the missionaries forced to leave town.15 That same year the home of some Latter-day Saints in Eugene, Oregon, was bombed with dynamite to try and drive them out of the area.16 A note on the building read:

“This is a warning to your tribe. You have tormented the public enough. Move on; the next shot will do more. We mean the Mormon tribe.”

In 1910 dynamite was thrown at Hotel Utah which caused Angel Moroni’s trumpet to fall from the Salt Lake Temple.17 And there were other such cases.

The hostility on the East Coast was part of a national swell in violence against Latter-day Saints that had been going on for years using or threatening to use dynamite.

The threats of further explosive violence against the Saints in New York failed to materialise.18 After receiving threats Walter contacted the relevant agencies to initiate an investigation. Yet he remained fixed in his determination to bring about the buildings in Brooklyn and to provide the Saints with the facilities they needed and deserved:

“This will not influence us in the least…We have too much confidence in the American spirit of fair play and the American belief in freedom of worship. We shall first build a home which will be used by me and my family and later shall erect an assembly hall for our converts.”19

The work continued unabated and in due course, the new Brooklyn chapel was built and completed, without incident.20 The building was subsequently dedicated by Elder Reed Smoot on 16 February 1919.21

The new chapel was a prominent feature in the area and became an important gathering point for Latter-day Saint members and missionaries.

Religious Freedom

Walter Monson penned an article for the Times Union a few days after the dedication of the Brooklyn chapel. The article was in response to one published by an anonymous author who was critical of the church and sought to whip up further opposition. In turn, William criticised those who had threatened to blow up Latter-day Saint buildings and their lack of tolerance of other religions. Of those opposing the Church he asked:

Under which clause of the Constitution of the United States would a law prohibiting proselyting by the Latter Day Saints by classified? The writer is curious to know.22

William was not willing to allow antagonistic and unjustified accusations to be levelled against the Church unchallenged. Despite risking the ire of people who had expressed a willingness to destroy Church property he called them out on their behaviour. With time those opposing the Church and its activities stopped and the Saints could worship and live their lives without fear of attack or destruction.

Education, communication, and patience can bring about peace in society, not reprisals or retaliatory threats of violence. In this case, the Saints followed the teachings of Jesus Christ and lived their lives in accordance with their beliefs.

‘To Build Church,’ Adams County News, 19 February 1916, p. 6.

‘President Monson Makes Report on Dynamiting,’ Logan Republican, 5 February 1916, p. 5.

‘New Church Blown Up,’ The York Dispatch, 21 January 1916, p. 1.

‘Church Dynamited,’ The Fulton County News, 27 January 1916, p. 1.

‘Church Dynamited,’ The Fulton County News, 27 January 1916, p. 1; and ‘President Monson Makes Report on Dynamiting,’ Logan Republican, 5 February 1916, p. 5.

‘Mormon Church Building Wrecked,’ Salt Lake Tribune, 22 January 1916, p. 11.

‘Dynamite Wrecks Church,’ The New York Times, 22 January 1916, p. 18.

‘Dynamite Mormon Church,’ New York Tribune, 22 January 1916, p. 4.

‘To Build Church,’ Adams County News, 19 February 1919, p. 6.

‘Elders in Pennsylvania,’ Deseret Weekly, 9 January 1897, p. 4.

‘President Monson Makes Report on Dynamiting,’ Logan Republican, 5 February 1916, p. 5.

‘President Monson Makes Report On Dynamiting Buck Valley Church,’ Deseret Evening News, 2 February 1916, p. 2.

‘Mormon Elder Answers Threats,’ The Daily Standard Union, 26 August 1916, p. 2.

‘Dynamite For Mormon,’ Times Union, 26 August 1916, p. 12.

‘Mormons Are Driven from Georgia Town,’ Salt Lake Telegram, 4 November 1908, p. 11.

‘Dynamite For Elders,’ Ogden Daily Standard, 20 June 1908, p. 2.

‘Three Men Repairing Damage on Top of Big Temple Statue,’ Salt Lake Telegram, 31 May 1910, p. 10.

‘Threat To Dynamite New Mormon Temple,’ The Sun, 26 August 1916, p. 4.

Ibid.

Brooklyn Chapel dedicatory services program, M255.86 B872e, CHL.

‘Passing Events,’ Improvement Era, Vol. 22, No. 6 (1919), p. 551.

'W. P. Monson, ‘Tolerance to Mormons,’ Times Union, 25 February 1919, p. 4.

James this was fantastic! Any chance you could work this into broader academic article?